Making Cutting Tools in New Ways

Horn began operations in 1969 with a focus on grooving tools. Today, it is represented in more than 70 countries and has expanded its tooling business to threading, interpolated milling, axial grooving, drilling, reaming and broaching.

One of the line items of my job description is visiting plants. In 20-plus years of doing this, I find that plants are as individual, well, as individuals. Whether it is a job shop, multi-generation production facility, captive or OEM, these facilities are unique, which makes each visit interesting, educational and almost always provides a story to tell. That’s where editors like me come into play to tell the story.

In the last few years, numerous metalworking OEMs have glommed the idea of holding technology events at their tech centers or plants. The proliferation has done wonders for the frequent flyer miles of editors. These trips are in addition to shop visits we make to users of the OEM’s products and services.

Featured Content

These events, which started out primarily as tours and demos of the host company’s products, have morphed into mini trade shows that feature the host’s supplier companies. Horn had 11 vendor companies participating in this year’s event. The advantage for the participants is a relatively captive audience, and it is succeeding. More than 2,200 visitors joined us at Technology Days this year.

Like most things, some companies do these technical events better than others. Having attended many of these events, I can say that Horn produces an exceptional 3-day event.

In the trade publishing business, we have an expression “Content is king.” Without timely, relevant and useful information, you wouldn’t read our magazines and visit our websites. We also have another expression, “Showing up is 80 percent,” so we pack the bag and head out.

In the Groove

Horn began operations in 1969 with a focus on grooving tools. Today, it is represented in more than 70 countries and has expanded its tooling business to threading, interpolated milling, axial grooving, drilling, reaming and broaching. More than 50 percent of the inserts Horn sells are specials, designed for a specific job.

Horn’s U.S. operation is headquartered in Franklin, Tenn., where it’s been since 1998. Shortly thereafter, it began machining inserts. The German operation is designed around cells with customized milling machines fitted with arbors that carry multiple grinding wheels to generate the various geometries needed for the company’s extensive product line.

The beauty of this cellular manufacturing system is that it is easily duplicated in other facilities, such as the Franklin operation. According to the company’s managing director, Lothar Horn, son of the founder, the U.S. operation is scheduled to double manufacturing capacity beginning this year because of the market’s strength and growth potential.

The Franklin operation, which now has more than ten of these manufacturing cells, is able to seamlessly switch between metric and imperial, based on customer specifications. Moreover, each of these cells is self-contained and uses custom material handling and measurement designed for quick change-over. This strategy allows much faster turnaround and speed to market.

Citing all of the usual reasons for making products close to the market—near sourcing, faster turn-around, better response time—Horn early on figured out that the U.S. market is a combination of metric and imperial measurement systems, and having the capability to generate both kinds of cutting tools domestically is a much more efficient way to go.

We Tourists

Before we got into the technical meat of this plant visit, we did the requisite plant tour. On this particular tour, we were given headsets tuned to the frequency of our stalwart guide Harold Haug’s microphone. His English is excellent, and the radio system worked perfectly, which made the tour informative and pleasant.

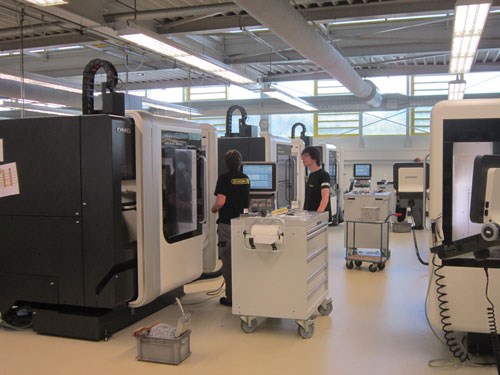

Our first stop on the tour was the demonstration area. Horn, like most cutting tool makers, keeps a stable of current machine tools in order to test and demonstrate their cutters. Builders including DMG/Mori Seiki, Hermle, Gildemeister, Traub and Tornos were represented on the floor.

Some of the machines are permanently used by Horn, while some were brought in for Technology Days event. Several of the technical topics that we learned about later in the presentations were shown applied on one or more

of these machine tools connecting the academic with the real world.

Starting at the Beginning

Last year, as part of an ongoing expansion program at the company headquarters, Horn completed expansion of its Horn Hartstoffe facility dedicated to the production of its carbide inserts. In this plant, “feedstock,” which is carbide, gets mixed with binder to be pressed into inserts that eventually find their way into shops around the world.

It’s a fascinating process with thousands of permutations covering the size of carbide grains, the binder material to carbide ratio and the method used to create the raw insert shape. Carbide grain sizes run from Nano 0.2 micron to extra-course 6.0 micron and every size in between. Add binder ratio percentages that likewise cover the gamut, and it becomes clear why the company’s catalog has more than 20,000 different products.

Some of the factors in insert production that justify all these “recipe” variations include designed for hardness different performance characteristics such as hardness and toughness. Vague as these terms are, the best blend of the two determines tool life and cutting ability in a given application. Moreover, the grin size is a factor in how sharp the cutting edge can be honed.

Once the ingredients are mixed, they are shaped using three different processes. An axial press is used for more basic insert forms and employs a die set to impart the desired shape of the insert. Because removal from the die requires a draft angle, more complex geometries require a different method.

To get around the draft angle issue, an extrusion process is used for more complex shapes. A specially developed formulation of carbide, binder and various waxes are used to create a mixture with a viscosity that can be pressed through the extrusion process.

The result is a precisely shaped ribbon of material that is then cut to the desired thickness for the “green” insert. Interestingly, this process uses a floating mandrel pin to create through-coolant channels in the blanks. The waxes and other additives are removed in a pre-sintering process further down the production line.

Injection molding is another process used at Horn to produce complex insert forms in higher volumes. The same formulation of carbide, binder and additives that is used in the extrusion process is used in the injection molding, which also requires a pre-sintering process to remove the additives before the inserts are ready for the final sintering process.

All three of these insert shaping processes are extremely abrasive on the dies and molds. For that reason, Horn Hartstoffe has a mold building and repair area within the new addition.

Next Step

The green inserts move on to the sintering stage of the manufacturing process, which is located in the main facility. Sintering is a thermal, chemical process that causes the inserts to reach their final unified hardness.

During sintering, the carbide binder mixture is heated in a vacuum auto-clave to between 1,350°C and 1,550°C with gas pressures ranging to 100 bar. In this process, the carbide binder mixture reaches a partially plastic stage in which the binder material is able to flow into voids between the carbide grains, eliminating pores within the insert, creating a homogenous unit.

Because the binder and carbide are in a flux during sintering, literally shifting around, carbide insert makers calculate a shrinkage factor between 20 and 22 percent between the green insert and the final sintered insert. These shrinkage calculations are factored into the die and mold manufacture.

On the Shop Floor

After undergoing a range of quality control procedures that test everything from density to harness to micro structure using scanning electron microscopy, the sintered inserts are ready to be ground to finished size and shape. The largest bay in the factory is devoted to more than 200 specially designed and milling machines.

Rows of these self-contained, highly automated machine cells impart the final geometry to the inserts. Built exclusively for Horn by DMG/MoriSeiki, the machines are basically CNC milling machines that grind.

On each machine is an arbor that carries various superabrasive wheels spaced in such a way that a simple Z-axis move from the spindle brings one wheel into the cut and another out. In effect, this setup functions as an automatic wheel changer.

Coupled with Horn-designed automatic load/unload material handling systems that use integrated measurement and counting devices, these cells can run lightly attended. Being a specialty cutting tool maker, the run volumes for Horn are relatively small. Flexible production methods allow it to compete with higher volume producers.

Put on your Coat

The coating process is the final step of the factory’s insert production. Not all inserts are coated, but many are. This is where various chemical mixtures are deposited on the carbide substrate to enhance cutting performance and tool life.

Two methods of deposition are used to lay these coatings on the substrate: PVD physical vapor deposition and CVD chemical vapor deposition. The company runs eight coating furnaces to create the PVD coatings. PVD coatings are deposited using a “sputtering” technique that provides an even and controllable coating thickness on the carbide substrate. Currently, the CVD coatings are sent out.

Investing in the Future

The last stop on the plant visit is an area dedicated to the company’s apprenticeship program. Like most facilities I’ve visited in Germany, Horn recruits and extensively trains its next generation in-house.

The company is currently training 50 apprentices in a dedicated, 1,200-square-meter area of the plant. These young people learn basic tasks and, according to ability and interest, move on to increasingly sophisticated operations. Some were already running five-axis machining centers.

Each year, the company accepts 15 candidates to the Horn Academy program, ensuring a good line of supply for future skilled workers.

Technical Topics

Taking the extensive plant tour turns out to be a good thing because it helps put the next phase of our visit into perspective. The technical presentations held each of the

3 days of the event are, well, technical.

Of the eight presentations, there were four that I consider most relevant to production machining. One of these is a discussion that focuses on the use of “high-feed rate” machining techniques. It compares and contrasts this methodology with the better known high speed machining.

Another interesting topic is the use of ultra-hard cutting materials. Its focus was on diamond cutting tools and CBN with a specific emphasis on the manufacture and use of mono-crystaline diamond for difficult, nonferrous applications.

The ability to electronically program various axes on a CNC machine has led to a proliferation of ancillary operations that were once only done as secondary operations. Broaching is one of these, and the presentation focused

on how to best apply broaching tools and techniques to CNC machines.

A presentation on customized tools discussed the

definition of custom tools and the decisions a shop needs to make in order to justify using them. It was a practical and useful approach to what is sometimes a squishy problem for the shop.

PM plans to run in-depth articles on these technical presentation topics in future issues. Please keep an eye out for them.

My trip to Horn turned out to be much more than a plant visit, but rather an experience not to be forgotten. The company not only successfully showed its visitors its in-depth process of creating carbide inserts via cellular manufacturing, but also revealed its devotion to hiring well-trained people, its dedication to teaching the industry about the technicalities of cutting tools and all the while allowing its company culture to shine through.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Cutting Tool Coating Production

This article looks at the coating methods available for carbide cutting tools.

-

When Thread Milling Makes Sense

Threading a workpiece is a fundamental metalworking process that every manufacturing engineer takes for granted.

-

Bar Feeder Basics

Some primary factors are often overlooked when considering how to justify the implementation of a bar feeder for turning operations.