Manufacturer Stays True to 106-Year-Old Niche

Finding a niche and sticking to it sounds like common sense. Sometimes, however, companies get distracted, even bored, with a niche. That’s never been a problem for the Fischer family.

“Remember what business you are in.” That pearl was imparted to me by Fred Fischer on a recent visit to his shop, Fischer Special Manufacturing in Cold Spring, Ky. For 106 years, third-generation Fred and his co-owner cousin Steve Fischer have never strayed from the business niche their grandfathers founded. The company started in 1905 at the dawn of the gasoline engine. The two founders were Fred and Steve Fischer’s grandfathers, one was a banker and the other a machinist—seemingly an odd couple for sure.

“It worked, however,” Fred recounts. “Back then there wasn’t much screw machining being done. The brothers developed a process to wind spark coils used in internal combustion engines, which is a turning operation. Sooner or later you have to attach a wire to the spark coil, so you need a brass thumb nut or some kind of fastener to hold the wire in place. With early customers such as Delco and Ford, we were in the nut business and we still are.”

Featured Content

During the depression, the company, like most, was in need of business, so they tooled up some machines to produce a hex nut. Steve picks up the thread and says, “They produced these nuts and attached a sample to an advertisement and sent it out as a capability promotion to prospective customers. No one had ever tried this, so they had to clear it with the post office. Well, it took off, and suddenly they got orders for nuts from all over. It helped keep the doors open.”

Half joking, Fred says, “We didn’t turn an external thread in this shop until Steve and I joined the company in the 1970s. Our fathers and grandfathers knew the business they were in.”

Making it on Multis

Fischer Special Manufacturing was and still is a machine shop focused on making screw machine nuts and connectors. “Our goal is volume production of these screw machine parts with precision and quality,” Steve says. “We want to feed an assembly line with our nuts and connectors. We serve automotive, appliance, plumbing, electronics, and most recently, medical. There is still plenty of work for a shop like ours. Because we are a dependable line of supply and close to our customers, we’ve been less impacted by outsourcing.”

The shop primarily works in brass, but also machines bronze, copper, aluminum and steel. Current employment stands at 55, and the shop is in the process of building a second shift to reflect the upturn in business for the past year or so.

Its five-spindle Davenport multi-spindle work ranges to 1.25 inches in diameter. Index single-spindle automatics and two Hardinge CNC turning centers give the shop capability turning as much as 2 inches in diameter. The milling department has two Kitamura CNC VMCs for production and secondary work.

The shop is climate-controlled, and the majority of machine tools in production are Davenport multi-spindle machines. According to company history, prepared for its 50th anniversary in 1955, around 1910 Fischer Special bought its first Davenport machine.

The day we visited the shop to interview Fred and Steve, all 39 of the current crop of multi-spindles were either running or being set up to run. It’s a busy shop, and the cousins know how to keep it that way.

From Shelf to Print

For much of Fischer’s history, the nature of the work produced was for commodity products (for lack of a better term). Inventory was held by the shop and orders filled from stock. That began to change during Fred and Steve’s tenure at the helm.

“We used to make products—nuts—that sat here until a customer called up and asked for a million of this or that, and then we’d ship them out,” Steve says. “And that model sustained the company for many years. However, we’ve seen that change as lower-priced producers entered the fastener field. We were getting pushed out, like many domestic producers at the time.

“So to compete, we had to look at different ways to satisfy customers,” he continues. “It led us into a new business model whereby we make parts to customer prints. So we went from a standard line of hex nuts and connectors to special fasteners and screw machine parts designed by the customer. We went from catalog offerings on our shelf to custom manufacturing to customer print.”

With its heritage of innovative marketing, remember the hex nut promotional campaign, Fischer used sales reps, print advertising and trade shows to get the word out on the shop’s newfound capabilities. “Interestingly, when we migrated from shelf to print, we found that many of our existing customers had the need for custom work, but up until then we were not participating,” Fred says.

However, the transition from commodity fastener production (the niche Fischer Special dominated for decades) to custom producer upped the ante as far as competition. Most of the volume production screw machine shops were in this business. “We became one of many instead of basically the one,” Fred says.

That required some serious revamping of technology and methods for the shop floor. For example, investments in various attachments to take advantage of the Davenport’s capabilities that hadn’t been needed for straight production work.

“The primary limit of the Davenport is size and complexity,” Fred says. “Their effective range is 0.125 to 0.875 inch. To have additional size capability, we got into CNC turning, which took us to 2 inches in diameter. The CNC allowed us to complement the high volume production work by being able to make more precise and complex workpieces and prototyping on the Hardinge turning centers. In addition, the factory training made the transition into programming much smoother for us.

“Of course, finding CNC operators and programmers is much less difficult than finding Davenport machinists, so the addition of a programming department wasn’t a big deal. Moreover, the programmers easily transitioned to the CNC Kitamuras when we put them in our milling department.”

The company uses its CNCs to develop a prototype for the customer and can quickly send them samples. Any modifications can be easily made on the CNC machines until a final part is approved. “Such back and forth would be difficult on the Davenports,” Fred says. Once the order is received, it goes to the multi-spindles for production. The cam machines and CNC machines work in concert to secure and produce custom work. The Hardinge machines are equipped with sub-spindles and auto-loaders and for shorter runs can be tooled for lights-out production. “The CNCs give us much more flexibility to be responsive to customers, which is an important part of the business we’re in,” Fred continues.

Getting Lean and Mean

“We’re currently running at the equivalent of a shift and a half,” Fred says. “We would hire more people if we could find them. Finding people who can run a Davenport is a challenge. However, using lean principles we installed a few years ago and common sense shop practices, we are more productive with the workforce we have than ever before.”

Of course, there are many factors upstream and downstream from the machine tools in a shop. In order to be more efficient in the custom business, some of the old ways of making parts needed evaluation.

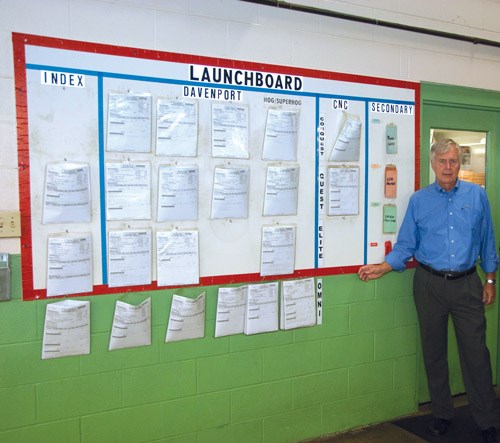

“We brought in a consultant to look at our workflow, and he suggested ways to get leaner,” Fred says. “One of the first things we did was replace the production control computers that were scattered around the shop. We replaced them with a launch board. New jobs in the production queue are hung on the board, and depending on the delivery date, the machinist is able to select the next job to run. We believe he has a better feel for what just came off the machine, and which job he’s tooled up to make next. It’s improved our efficiency.

“Another lean initiative we instituted was to streamline our material storage and delivery to the machines,” Fred says. “Using overhead cranes, one person can deliver bundles directly from the loading bay to the machine, if necessary. With the lean practices in place, we only need a total of one and half employees for handling raw material and chip removal. We single-source our stock purchase, and because we run a lot of brass, we are on JIT with the supply house. Being able to bypass the storage racks manes, we need less material on hand. We’ve reduced our stock on hand by a third.”

Price vs. Cost

Most of the parts that that Fischer makes go into larger, more complex, assemblies. Regardless of the industry, failure of a 5-cent nut can cost a supplier many times the price of the nut. “We can get a slight premium for our parts, because we put the quality into our processes, and the customer knows it’s in there,” Fred says. “Moreover, if there is a problem, they know we will make it right. You can be a low-cost producer even though you’re not the low-priced supplier.”

About half of the Davenports on the floor are dedicated to specific customers. Using a push/pull system, they can draw down parts as they need them. The machine runs various parts for the customer. Some have three machines dedicated to them, and if the customer needs to change an order, the system allows them to reschedule the work to accommodate the change. “They basically own those machines,” Steve says.

The operators know the jobs, and by virtue of the lean launch board, are empowered to run jobs in sequences, such as families, in the order that makes the most sense economically. Doing this reduces setup time, which saves both the customer and Fischer Special money.

Have Work—Need People

Fred believes there is a stable future for the kind of work his company does. “Manufacturing is not dead,” he says. “But it’s going to be different. Much of the off-shoring has slowed significantly as it becomes apparent, that doing business overseas is more difficult and costly than anticipated. Customers are losing patience with parts produced incorrectly that requires re-work or even replacement. It can be an expensive fire drill. I don’t lose sleep over getting work in; I lose sleep over finding qualified people to get the work out.”

This company and this family have remained focused on their niche. True, changes have occurred in the parts and processes as markets rise and fall and are replaced with others. That’s the nature of metalworking, but what sets Fischer Special apart from many is how they manage to respond to change by using their heritage of confidence and competence to good use.

RELATED CONTENT

-

The Evolution of the Y Axis on Turn-Mill Machines

Introduced to the turn-mill machine tool design in about 1996, the Y axis was first used on a single-spindle, mill-turn lathe with a subspindle. The idea of a Y axis on a CNC originated from the quality limitation of polar interpolation and the difficulty in programming, not from electronic advances in controls or servomotor technology as one might commonly think.

-

A New Approach to CNC Turning

This turning process takes advantage of a turn-mill’s B-axis spindle to vary a tool’s approach angle to optimize chip control and feed rates.

-

How to Get More Efficient Production from Swiss-Type and Multitasking Machines

SolidCAM for multi-axis Swiss type and multitasking machines provides a very efficient CAM programming process, generating optimal and safe Mill-Turn programs, with dramatically improved milling tool life.