Part cleanliness isn’t always a priority in many shops. However, when suppliers are compelled to adhere to cleanliness requirements in order to satisfy their customers, they are more likely to use the equipment and processes necessary to do so.

Although not every shop has been affected by cleanliness specifications, many suppliers to automotive OEMs are already complying with stringent cleanliness standards. North American OEMs such as Ford Motor Co., and in turn, their suppliers, have been required to comply with the ISO 16232 standard since 2005, when it was first put into effect.

Featured Content

“All automatic transmissions use precision-manufactured electro-hydraulic components with very small clearances,” says Lev Pekarsky, technical expert on contamination and filtration for Ford. “Presence of even small-sized debris in those systems could cause degradation of transmission function such as shift-engagement quality. That is the reason Ford and our competitors have been continuously improving cleanliness of all transmission components.”

As part of its long-standing culture of global competitiveness and fiscal responsibility, Ford says, it began developing its own contamination engineering requirements or specifications in 2001. These specifications are based on the German automotive standard VDA 19, on which ISO 16232 requirements are based. Ford’s engineering specifications include exceptions to the ISO standards, however, and answer additional questions that are required to integrate ISO into the Ford Production Quality System.

Pekarsky says Ford’s specs are detailed. “They answer questions such as what solvents to use, what is the parts collection process and what is a part’s disposition (scrap or reuse) after inspection.” He says they also outline for the user the special extraction (wash-down) procedures for individual sub-assemblies, and they explain how to calibrate a scanning electron microscope (SEM) for material identification.

Pekarsky explains that most OEMs, including Ford, conduct regular contamination inspection of transmission components in production using transmission plant contamination labs. The Ford Transmission and Driveline engineering organization also has its own product development contamination lab in Livonia, Michigan, that is responsible for developing new, advanced contamination inspection procedures and supporting special investigations.

Ford specs include different stipulations for different types of transmissions. The small parts that make up the transmissions, such as valves, springs and gears, also are tested for particle contamination, mostly by Ford suppliers prior to shipping. Very detailed specification documents not only contain inspection process descriptions, but also include requirements for inspection system cleanliness prior to testing. Requirements defining the maximum number of particles and corresponding particles sizes for different types of components being tested are also included.

Lab inspectors rely on the company’s contamination specifications to do its job every day, Ford says, and following these standards saves money on warranties and rejected parts.

Evolutionary Requirements

Ford says its contamination specs, along with those of other OEMs, have evolved through the years and continue to be updated when new contamination inspection technology becomes available. The first specs written by Ford engineers many years ago were based on gravimetric methodology, or the weight of debris on a component. Clean filters were weighed prior to debris collection and “dirty filters” after debris collection. The “after-minus-prior” filter weight difference had to adhere to specific requirements, Ford says. Most of the parts in the transmission were required to be tested.

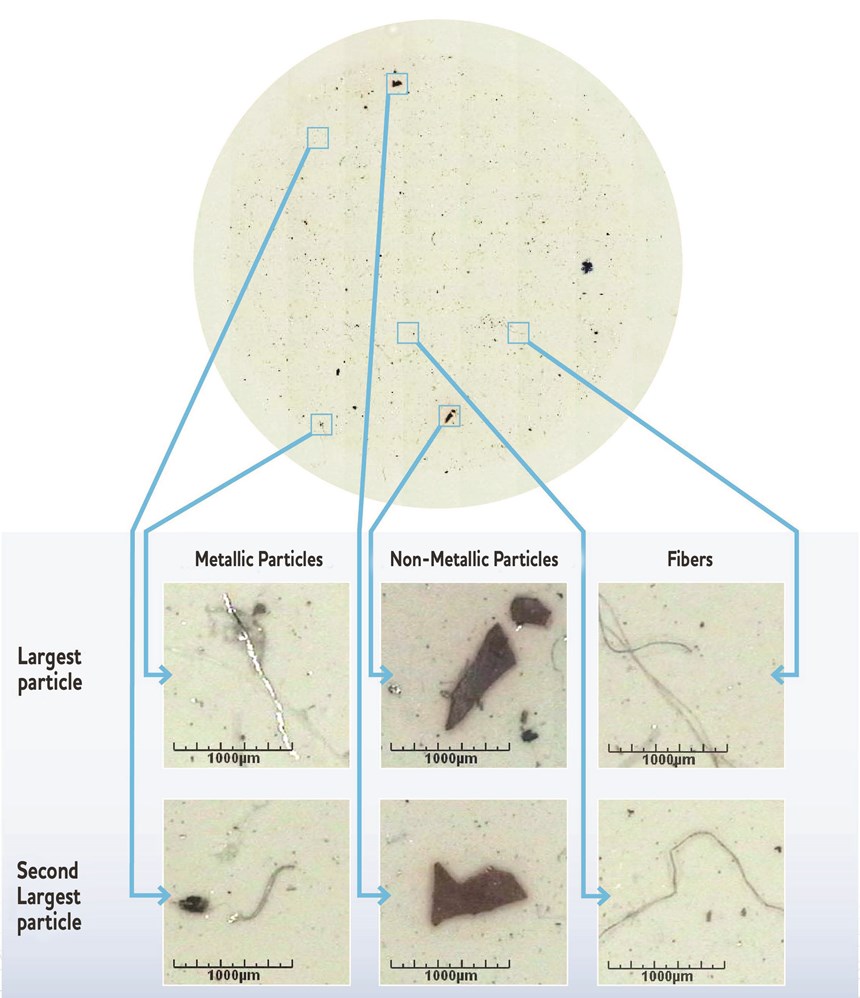

Then, about 10 years ago, optical detection became possible using automated microscopes to capture and analyze digital images of debris collected from manufactured parts.

“The software (that was packaged with the microscopes) became so sophisticated that it now can differentiate between filter background and individual debris, identify metallic and non-metallic materials and measure their sizes and calculate quantities,” Pekarsky says.

Around 2013, the Livonia lab began using cleanliness analyzing microscopes from Jomesa North America Inc. designed and produced solely for microscopic filter analysis. Jomesa has since introduced optical systems to Ford’s contamination labs using hardware and software to detect metallic particles using a patented automatic polarization method.

A Strong Partnership

According to Peter Feamster, product management director for Jomesa, Ford and Jomesa have been working together since 2010 to develop standards for Ford to follow internally. The automaker’s engineers developed standards and debris particle size limits based on the company’s own cleanliness manufacturing processes, then, over the past two to three years, Ford started cascading these standards for its suppliers to follow as well. The Ford specs are not Jomesa-specific, but they reference Jomesa models as examples of ISO/Ford engineering specification compliant systems, Ford says.

Not all particles are easy to detect and measure, however. “The biggest challenge of optical systems is when you have a white or translucent particle, say aluminum oxide or glass, they can’t be detected by an optical microscope,” Pekarsky says. “Ford and a few Ford suppliers introduced the use of automated SEM in addition to automated optical microscopy (AOM) for contamination inspection of the most critical components.”

According to Feamster, Jomesa has developed a Ford-specific database for suppliers to report the cleanliness data in a standard way that engineers can analyze efficiently. “This system was designed to be common among all Ford suppliers, so they are all looking at the same information across the board.”

Microscopes Designed with Cleanliness in Mind

Ford houses two Jomesa AOMs per transmission contamination lab, Feamster says. There are four labs located in North America, plus one in China and one in Mexico.

Unlike other inspection equipment suppliers, Jomesa designs its systems only for technical cleanliness analysis, it says. The company says it is dedicated to this specific industry niche and focuses all its efforts on constant improvement.

The microscope software that is responsible for the measurement and recording, called PicEd, is continuously being updated and improved, Jomesa adds. It also has free upgrades, and anyone around the globe can download the latest version without a service contract. The Ford plants in China and Mexico have the same access to the same software as those in North America.

Feamster says, based on Ford user feedback, automation is a favorite feature, much because the systems are so easy to use, with microscopes that feature computer numerical control and a digital camera. “The system can be mastered by anyone who is not super-skilled in microscopy,” he says. “Users only need to follow instructions and go through a small amount of training.”

The systems also allow review and editing of test results. All edits are logged to facilitate audits of the testing process.

Customer support and training are the highest priority for Jomesa North America, according to Feamster. If there are complaints or suggestions, the company implements changes based on this feedback.

Clean Parts Are Critical

Most new car buyers probably don’t think about how the cleanliness of the transmission and engine components can affect the way the car operates. Twenty years ago, they may not have known that a problem with a car was caused by dirt particles that may have already been present in the car’s parts when it was brand new. Companies such as Ford and Jomesa that are working behind the scenes to improve cleanliness specifications and part cleanliness inspection are helping car buyers get a lot more mileage out of their investment these days. More time between oil changes and less maintenance in general can be attributed to cleaner parts in transmissions and engines.

RELATED CONTENT

-

The Dirt On Cleaner Crankshafts

A high-pressure waterjet blasts away burrs and machining residues that resist more traditional cleaning methods.

-

How Eaton Uses Metal 3D Printing

With the ability to address customer needs faster and iterate parts quickly, this metal 3D printing system is now standard within the workflow for both the engineering and toolroom teams.

-

Single Pass Honing System with Automatic Tool Wear Compensation

Single pass honing, also referred to as diamond bore sizing, is a good way to produce parts economically when the bore is small or has thin-walled members that need to be honed.