It's Only A Number

A person’s age is often said to be only a number, with overall health and fitness being the truly significant measures. Cutting fluids, like all industrial lubricants, should be held to the same standards—it really is condition that matters. By focusing on that philosophy, a shop can achieve immediate, sustainable cost savings.

#metalworkingfluids

A person’s age is often said to be only a number, with overall health and fitness being the significant measures. Cutting fluids, like all industrial lubricants, should be held to the same standards—it really is condition that matters. By focusing on that philosophy, a shop can achieve immediate, sustainable cost savings.

Twice a week, on average, we get an urgent call from a lube manager, plant manager or someone else with maintenance or operations responsibility. A mandate has been issued by higher-ups to reduce costs, typically by 3 to 5 percent or more.

Featured Content

By the time we receive these calls, the mandate generally has some moss on it. The caller has been sitting on the directive, weighing his options and postponing the dreaded paperwork. The “deadline” for his response is looming, and he needs a strategy.

Fortunately, that’s the easy part. Outlining and thoroughly documenting how to achieve a 3-, 5- or even 7-percent savings is relatively straightforward—particularly if the company, like 90 percent of industrial lubricant users, changes fluids according to the clock instead of the condition. It’s even easier if the user is regularly adding fluids to compensate for leakage.

A New Perspective

Sound lubricant management starts, easily enough, by changing how we think about the lubricants themselves. For many companies, lubes are a consumable commodity: Buy at the lowest cost, discard after a specific number of hours of service, replenish as necessary to make up for spills and leaks. A better approach, though, is to treat them as assets, with attention to how they’re stored, dispensed, monitored and replaced. Overall costs will decrease—often substantially so, and virtually always enough to meet that pesky mandate. Following are three areas that deserve particular attention.

Storage: Lubricants degrade when storage practices are an afterthought. The most common storage problems are damaged or improper containers, condensation, dirty dispensers, exposure to dust or fumes, poor outdoor procedures, mixing of different products, exposure to extreme temperatures, and going beyond recommended shelf life by failing to follow a FIFO (first in, first out) usage policy.

Handling: When it comes to lubricant handling practices, one of the most grievous issues comes from the use of improper containers for lube top-offs. These containers allow water and other contaminants to enter, shortening the life and effectiveness of the fluids.

Monitoring: If it’s an asset, it’s worth tracking. Lubes belong in tanks, not in absorbent socks, and shops need to know how much oil is making its way to the latter and how much make-up is needed as a result.

When consumption is quantified, the results are always surprising. It’s not uncommon for “small” leaks throughout large manufacturing facilities to total as much as 15 barrels of costly lubricant every month. While this is never good, with the current high price of oil, many plants could buy a new tank or forklift with 1 year’s savings in lubricant, absorbent and associated disposal costs. Proper monitoring is an easy way to reduce costs while sacrificing nothing.

Monitoring provides a baseline with which to benchmark improvements. It offers an HFI (hydraulic fluids index) and provides all the players—maintenance supervisors, company management, purchasing department and others—with a number for planning and operating purposes. And for those pursuing ISO 14001, tracking of lubricant against disposal is a requirement for certification.

The Heart Of The Matter

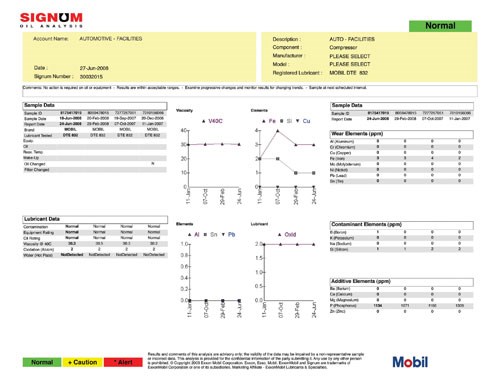

After implementing good storage and handling procedures and identifying baseline numbers, serious changes can be made. The most effective way to add life to oils is to let science, rather than a calendar, determine when they should be changed. Standard tests including BN (base number), AN (acid number), RPVOT (rotating pressure vessel oxidation test), and others (such as those that measure particulate contamination, corrosion performance or viscosity) all help flag the point where fluids begin to degrade. These tests can also be used to predict this critical juncture, making them valuable planning tools as well. Any oil use point can be sampled and monitored in order to base change-outs on oil condition rather than time in service.

For a vast majority of machines and applications, the cost of even the most comprehensive testing is significantly less than the labor and recharge costs—and loss of production time—of replacing fluids prematurely. For those companies that have implemented company-wide “green” initiatives or environmental policies to minimize waste, extending fluid service life, stopping automatic discarding of fluids that still have useful service life and reducing the volume of lube-soaked socks will go a long way toward the goal.

A related issue is the desire of many companies to reduce the use (and disposal) of zinc-containing products. The HFI referenced earlier, and the strategies that can be implemented as a result, can produce substantial cost savings and offer better performing alternatives to products containing zinc and other heavy metals.

Next time you’re feeling older than your years, let that feeling serve as a reminder to consider the condition of your fluids. Are you getting as much life out of them as you should? If not, take action and put measures in place to trim costs. And put down that donut; some crumbs might fall into the barrel.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Metalworking Fluid Management and Best Practices

Cutting metal is a complex process involving many critical factors to be successful. Correctly applied metalworking fluids, including oils or coolant, is one of these critical factors.

-

Considerations for Machining Exotics

In manufacturing, the term “exotic” is used to describe materials that display excellent wear characteristics, durability and service life in high heat, extreme cold or corrosive environments.

-

Preventing Metal Corrosion with Metalworking Fluids

All manufacturers deal with metal corrosion and rust. Learn about the causes of metal corrosion and options for preventing it.