Nobody knows one’s business better than the people who work there. The ownership, management and workers deal daily with the many pluses and minuses that comprise any and all companies, especially those companies trying to make a living in the rapidly evolving world of precision machined parts manufacturing.

While there are many anxious third parties standing in the wings to help shops transition to new and better ways of manufacturing, sometimes the best answers may lie within the shop’s own four walls. That sums up a core philosophy at Vanamatic Co., located in Delphos, Ohio.

Featured Content

Vanamatic is a third-generation, 90-employee precision machined parts manufacturer that takes pride in the company’s self-reliance and problem-solving capabilities. The management looks internally for answers first, involving employees in the problem/solution exercise and only afterward looking to outside resources necessary to fill in any gaps.

Through the years, employing this “doing more with less” approach has shown that with an environment that is focused on tapping internal talent first, answers come more readily and with the added benefit of buy-in from the employees. It’s a successful formula that has allowed the company to weather many storms since its founding in 1954.

The company’s latest major system integration move involves automating several operations with the use of collaborative robots (cobots) that can work independently or act as a sidekick in cooperation with a human worker. Cobots are a relatively recent development and one that makes robots much more practical tools on the shop floor, especially one as crowded as Vanamatic’s.

A Good Beginning

Through the years, Adam Wiltsie, plant manager, has engineered and developed labor savings, and process enhancements throughout the shop. One such device started out as a combination parts cleaning and accumulator carousel.

It has morphed into a machine-assigned gaging station, equipped with the proper gages needed for the parts being produced. It is linked to the shop’s central ERP system, giving the operator’s real-time status information and access to setup, measurement and job run information at their fingertips. These units were designed, built and integrated in-house.

Wiltsie has also spearheaded pick-and-place automation for loading and unloading for both lathes and mills on the shop floor. Basically, these units were mechanical shuttle loaders/unloaders designed to relieve the monotony of using an operator to perform the tasks. They were pretty much fixed automation with little flexibilty.

Robots represented a logical move forward for Vanamatic. After seeing a cobot (a robot with proximity sensing capable of safely working next to a person) being demonstrated at a trade show, Wiltsie could see the technology had caught up with his shop’s need. A six-axis articulated arm, working next to an operator, without the need for a safety cage was perfect. And Rich Lindeman’s assembly station was a perfect place to start.

Vanamatic’s first cobot was Ethel. She was named by her handler, Lindeman, who recently celebrated 50 years of full-time service with the company. For the assembly operation that Lindeman and Ethel were paired to do, perhaps Lindeman saw himself in the roll of Lucille Ball and his cobot as her stalwart friend, Ethel Mertz, working the chocolate candy conveyor.

The assembly task that Lindeman would have performed is an eight-step process that starts with a pallet of 144 parts. Lindeman picks up the part, checks a critical length measurement on a gage, assembles a small O-ring on the end of the part, blows out the ID, pushes a spacer over a set of threads to seat against a hex, verifies the assembly and places it in a package for shipping.

According to Wiltsie, Vanamatic’s plant manager, “Rich has no problem doing this and has successfully done this job for some time. It’s not a matter of performing the task once; it’s a matter of performing it 500,000 times, which was the order quantity for this assembly,” he says. “It’s a line-ready part for a fuel injection system and has to be right. I’m only 40 years old and did the assembly myself. I was achy after a few thousand and with less than perfect quality. Meaning no disparagement of Lindeman, assembly for this particular order was not intended for a human, and as I found out, was not humane, either.”

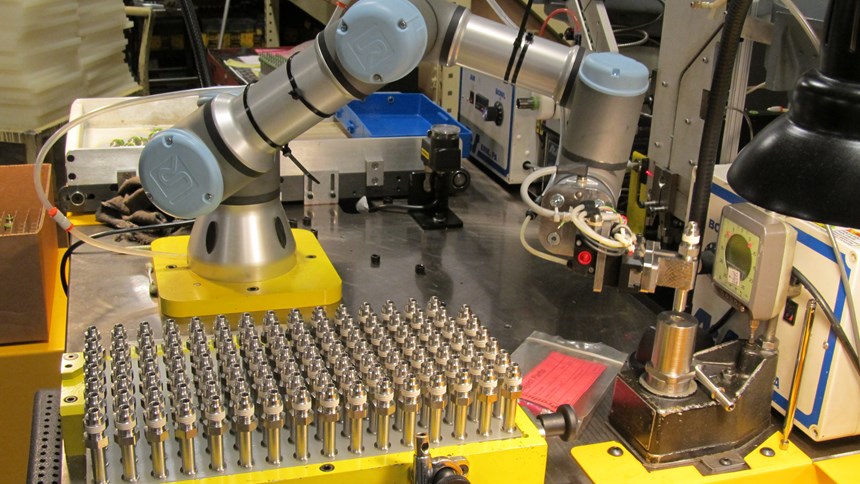

Ethel is a UR3 model built by Universal Robots. It’s the smallest cobot UR makes and has a range of motion that is almost equivalent to a human’s. The payload is 6.6 pounds, radius reach is 19.7 inches and the footprint for the unit is 5.9 square inches. However, for Vanamatic’s fuel injector assembly application, the robot was only the beginning.

Ergonomics are an important consideration for arranging a workspace for a human worker. Considerations include where the work enters the activity zone, placement of ancillary equipment such as measurement gages for this assembly operation, where the O-rings and spacers are placed in relation to the assembly activity and orientation of the machined parts as well as the location of the outbound packaging.

While ergonomics are important for Lindeman, it’s of critical importance for Ethel. She is smart, but lacks the ability to make subtle motion change decisions and the intelligence to adapt beyond her programming, even though she does include subroutines to deal with missing O-rings or spacers. That will be solved with vision systems in the future. Meanwhile, the use of “poka-yoke” for the incoming trays is a simple, reliable means of making sure Ethel’s program gets off to a good start in the right spot every time.

Vanamatic engineers use CAD modeling to illustrate various aspects of the manufacturing process such as plantfloor layout, machine simulations and other graphic and virtual representations of areas within the company. These skills were applied to preparing the work area for Lindeman and Ethel. The engineers can see it, run it and “what-if” test it before anything is built or bought.

“The programming tools for the cobot are extensive and well designed for ease of use,” Mr. Wiltsie says. “We brought our well-honed, in-house ability to design and build the working environment for the cell to the party. Our ability to integrate the cobot into a system that included the eight operations needed to assemble the fuel injector part saved the company a considerable amount of investment. Another advantage is that with our in-house design and build capability, we can easily make changes and improvements as time goes by.”

Today, Mr. Lindeman’s assembly operation consists of two steps by Lindeman, loading the pallet and packaging the finished part. Ethel does the six operations in between. They have a great relationship.

Encore

The installation of Ethel at the shop has been a success. It is doing its assembly job with no complaints and most important, no bad parts shipped.

A second cobot, also a UR3, arrived at Vanamatic less than a year after Ethel. Named Roxy by her handler, Gene Dickman, her assignment was more straightforward than Ethel. Basically, she tends to the needs of an Omni-Turn lathe, loading it with blanks and removing finished turned parts.

For this operation, it’s Roxy’s flexibility that is her strength. The Omni runs parts that are lower volume and higher mix. The ability to quickly change programs and end-effectors (grippers) is a key to her success.

With this application, the company called upon its in-house engineering to design and integrate the double gripper, so Roxy only needs to enter the machine once to load and unload its parts. The small footprint and relatively light weight of the robot (24.3 pounds) enable it to be mounted easily on the front of the Omni-Turn. Shop engineers drew up and fabricated the custom mounting brackets that integrate the machine and Roxy. They also wrote the interface software that enables the robot and machine to communicate.

Learning by Doing

Education is cumulative. Generally, people learn new things by building on the base created from previous lessons they have been exposed to.

That is the case for Vanamatic’s third cobot installation, Rocky. Rocky hit the shop floor about 196 days after the company integrated Roxy, and as the learning curve for integrating these machines and the necessary ancillary equipment sped up, the time between projects shortened.

Rocky, named by his handler, Paul Meiring, is another UR3 model from Universal Robots. “We applied what we learned from the first two cobot applications when getting Rocky up and running,” Wiltsie says.

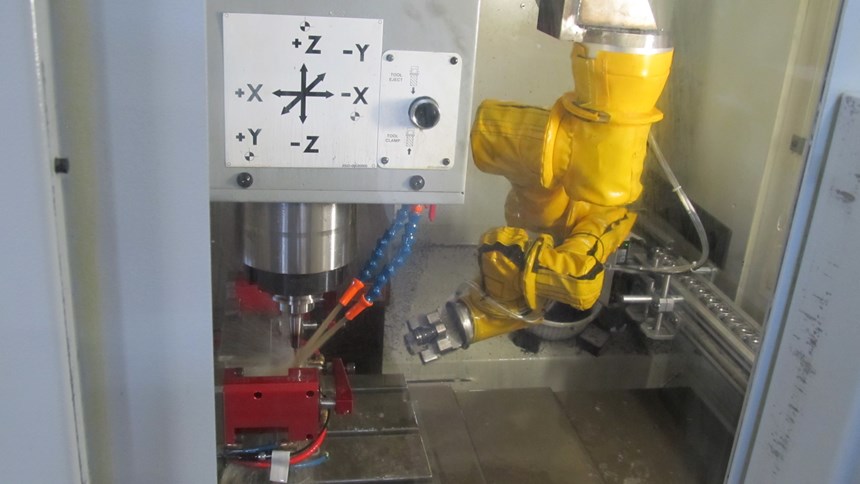

The task chosen for Rocky was another machine tending job (this time on a VMC) that is more complicated than Roxy’s. Like the other two applications, Vanamatic engineers made a virtual model of the operation including orientation of incoming and outgoing part conveyors.

For this loading job, the cobot needed to be placed inside the machine’s workzone to eliminate opening and closing the door. Because of tight confines inside the machine, Rocky is mounted upside down and attached to the machine column by a bracket designed and built in house. Part blanks are loaded onto conveyors located outside the guarding and deliver part blanks to Rocky.

Rocky picks the part blanks from a fixed location on the conveyor, but has the additional duty of moving the workpiece to a second clamping station on the workholder. Timing between the cobot and the machine CNC was programmed by Vanamatic using communication between the robot and the machine.

After the part is machined, Rocky verifies each part using an in-process Cognex gage before releasing it to the outgoing conveyor. The cobot is programmed to offload any rejected parts into a separate bin and, if there are three consecutive fails, it will alarm.

“This installation is a step forward from our VMC loading,” Wiltsie says. “Compared with the shuttle loaders we previously integrated into our VMCs, the flexibility of the cobot system we now enjoy represents a commitment to our future business growth.”

Surprising Source for Help

As Vanamatic management moved forward with the integration plans for the shop floor, it came across an ally that many might not consider. The company, like most, has dealings with the Bureau of Workman’s Compensation (BWC). Sometimes those dealings can be less than cordial because of the BWC regulatory enforcement role.

However, in the case of this cobot installation project, a kindred spirit was found in the BWC. In the state of Ohio, the BWC has grant money available for businesses to help them reduce potential workers comp claims by means simple and complex.

The shop applied and was awarded grants for its automation efforts, which significantly contributed to the expense of purchase and installation of its cobots. While such grant offerings might not be available in all states, it can’t hurt to ask.

Whether the shop is looking at systems integration using automation or communication or better workflow techniques, justification of the shop floor is not about worker replacement. Rather, it involves worker job enhancement. Wiltsie and the Ohio BWC seem to agree on the point that sometimes industry-wide recruitment issues can be less about the people and more about the jobs that are being asked of us to do.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Smart Workholding Device Measures and Monitors

Sensor and IIoT technology combine to enable these chucks and mandrels to automatically monitor workholding parameters and measure part features to ensure process stability.

-

10 Smart Steps to Take Toward Recovery

With many manufacturers facing challenges in light of the novel coronavirus pandemic, these 10 steps can help position manufacturers to find success.

-

Job Shop Automation: Fast, Simple and Agile

When done right, automation can provide important benefits. Here’s a look at automation options to suit the varying needs of typical job shops.