The Pursuit of Perfection

The “Pursuit of Perfection” is how Acero Precision defines its mission and while such lofty words make nice copy, all one needs to do is visit this contract manufacturer to experience how serious the company is about the technology, personnel and processes necessary to make it more than an abstract goal.

#workforcedevelopment

As the accompanying photos illustrate, Acero Precision is not an average metalworking shop. The lobby alone compares favorably with many four- and five-star hotels I’ve stayed in. And the rest of the shop is equally impressive.

Located near Philadelphia in Newtown Square, Penn., Acero Precision is a 25- year-old machine shop founded by President and CEO Michael Fitzgerald. Its customer base includes companies in the motor sports, medical (mostly spinal orthopedics), gas analysis and the underwater cable connector markets. That’s the company’s race car displayed in the company’s lobby and yes, they race it.

Featured Content

Acero employs 75 people and has experienced an average 20 percent year over year growth rate for the past 10 years. “Even in 2009, a down year for most manufacturers, we had our people working 10 to 15 hours overtime,” Mr. Fitzgerald says. “Today we would be running non-stop 24 hrs per day, 7 days per week if we could hire more people with the right skill set.”

Humble Start

Mr. Fitzgerald started his metalworking career in high school working summers in a relative’s machine shop. “The money was good and I found that I was good at machining,” Mr. Fitzgerald recalls. Bitten by the bug, basically his career path in manufacturing was set.

After high school, Mr. Fitzgerald enrolled in Drexel University pursuing a double major in mechanical engineering and finance. “Drexel is a co-op school so the pattern is to attend classes for 6 months and work for 6 months,” Mr. Fitzgerald says. “The school is designed to teach people to go to work. Well my first two co-ops were at relatively large corporations (Franklin Mint was one), and I learned that corporate culture was not for me. For my last co-op, ’I went back to work at the machine shop from my high school days where I augmented my machinist experience with quoting work for the shop.”

But even before Mr. Fitzgerald graduated the shop ran into problems making payments on two Mazak Quick Turn lathes it had purchased and the bank was threatening repossession. “This was around 1984,” recalls Mr. Fitzgerald. “So with no money, credit or even my degree, I convinced the bank to allow me to take over the payments on the machines. They figured there was nothing to lose and I figured this could be the start of my company. We never missed a payment.”

With a cardboard box for a desk and his dorm room as the shop office, Acero began. Upon graduation, Mr. Fitzgerald leased some space in Newtown Square, moved in the Mazaks and the rest is history—a very successful history.

Cellular Manufacturing

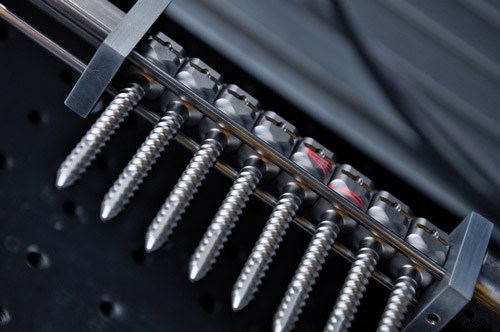

Acero’s stable of Star CNC Swiss-type machines, Mazak multitasking and horizontal machining centers are arranged in cells. “We arrange the cells with like-sized machines,” says operations manager David Watson. “Our three Star SR-10Js make up one cell. We have two 20-mm cells each with three Star SR-20RII CNC Swiss another and three Star SV-32 32-mm machines make up our fourth. We schedule the work across these machines by size. Currently we have a total of six machining cells including a four-machine Integrex cell with each machine having 80-tool capacity.

“Grouping the machines this way simplifies processing and throughput. The cell members become familiar and proficient with the machine’s capabilities, and we achieve much higher efficiencies with common tooling, programs, workholding and raw stock,” says Mr. Watson.

In the early 1990s Acero began phasing out its standard turning operations and replacing it with CNC Swiss. “We started buying Star machines and over the years have probably purchased 35 to 40 machines as productivity improvements have been added to the line,” Mr. Fitzgerald says.

“Implementing Swiss technology was a competitive key for the shop because the improved efficiencies from dropping a complex part complete helped offset price reduction demands,” says Mr. Watson. “As these machines continue to evolve, so does the productivity we can achieve. That’s why we continuously upgrade equipment on the shop floor.”

The cells are manned like a small business. There is a cell leader who effectively manages the cell. The cell leader is a manufacturing engineer who is responsible for everything that the cell produces including scheduling, ordering material, tooling, quality and work instructions and personnel

assignments.

When a job is scheduled to run, a manufacturing engineer assigned to the cell does the setup. To accommodate flexibility, efficiency and limit setups and tear downs, the cells are scheduled with a mix of long and short-run jobs. Generally, lot sizes run from 3 to 30,000 pieces. “On our Integrex cells for example, the 80 tool capacity of the machines allows us to keep three to four setups in the tool changer at any one time for quick change over,” Mr. Watson says.

“What we’ve found over the years is matching the tasks needed to be performed with right skill sets is vital to the cell operation,” says Mr. Watson. “For example, most of our technical people don’t have an interest in managing. Too often, people get promoted out of what they are best at and happiest doing.”

Once the setup is complete and proved, a Class 1 machinist runs the job making tool offsets and checking parts as the run progresses. Often this machinist is running more than one machine in the cell. Backing up this machinist is a Class 2 machinist who is responsible for running the job.

Acting as a sort of shopfloor “free safety” is a manufacturing assistant who is not assigned to a specific cell but fills in when and where needed.

However, as I learned from my discussion with Mr. Watson, the actual running of the job is sort of anti-climatic because of the work done on the front end in preparation for machining. Mr. Fitzgerald says it this way: “Develop a process, then stick to it. Details mean everything. This is a micro business.” As I was about to learn, he’s serious about this.

Necessity: Invention’s Mother

To say that Acero’s culture is quality minded is a gross understatement. This shop is obsessed with it. Moreover, they have constructively done something about it for more than 20 years.

It starts with dedication to making all parts to print. Now that may sound rather basic for a precision machine shop, but according to Mr. Fitzgerald, compliance with the print is rarer than one might think. “We have been so busy that we’ve farmed out some simpler jobs to other shops. I’ve been amazed at the high percentage of non-compliant work we get back. Non-compliance to the print is simply unacceptable here.”

So how does Acreo accomplish making its parts to print? According to Mr. Watson it’s a proprietary shop management system with the innocuous sounding name of “Sponge” and it serves as the central nervous system of Acero.

“It started out 20 years ago as a means to help our cell managers and machinists check parts accurately and reliably,” Mr. Watson says. “From that, it has become a full-blown manufacturing resource planning system. While there are commercially available modules that can do some of what Sponge does, none have bundled all the capability we have into a single database. It’s certainly one of our biggest competitive advantages.”

Mr. Fitgerald remarks that he’s probably spent more than $500,000 developing this system over the past 20 years. “No, I don’t run a cost benefit analysis for Sponge, but without it I don’t think we’d be as successful as we have been.”

Development of the system is ongoing. Acero employs a full-time IT programmer to refine the multiple functions that Sponge can perform. It’s a little like wish fulfillment for manufacturing—“think wouldn’t it be neat if we could….” Sponge is about fulfilling that wish. This interaction between machinists and IT results in a system that is friendly to the needs of manufacturing personnel.

Mr. Watson walked me through a few examples of what the system does to assure 100 percent compliance of the parts Acero ships to its customers. First off, every work station has computer terminal, keyboard and mouse accessible to the cell team members. This shop is so clean that hardened computer hardware is not necessary. The computer terminal might as well be in an office.

Each machine is listed on the system as being in one of thee modes: setup, run or maintenance. After the cell manager has ordered the tools and materials for the job, they are confirmed as on-hand and the job is setup. Only the materials necessary for the job are in the cell area at a given time.

“Cleanliness highlights anything that is “out of place” and this concept flows through quality,” Mr. Fitzgerald says.

In setup mode, the cell leader runs two parts for first article inspection (FAI). Using the electronic inspection gages arrayed on the cell bench, every dimension of the print is measured and entered into Sponge. If the inspection passes, the machinist logs on to the system and the machine goes from setup to run mode. Sponge then automatically sends an e-mail to the QC department, which then audits the cell leader’s FAI, and his designated inspection protocol.

Part of the setup is entering cycle time and parts count data, which sets the frequency of inspection necessary for SPC. It’s all within the machinist’s eyesight and uses green, yellow and red alerts to signal the machinist. If a dimension is trending out of spec, the system tells the machinist to make an offset adjustment for that tool. “We take the customer tolerance and cut it in half to run in a 50-percent band,” Mr. Watson says. That’s how we can generate a reliable CPK.”

Another nifty feature of this system is used for long runs. “Let’s say a job is set to run for 10 days,” Mr. Watson says. “After initial FAI the system calls for another FAI 5 days into the run.” An e-mail is automatically generated telling the cell leader and QC that another FAI is needed. In run mode, the machinist may only check 10 to 15 dimensions compared with 75 checked on the first article inspection. A new FAI during a long run assures that good parts are running for the 5 days, and if there is a problem it can be corrected before all the parts are run.”

Another example of machinist friendly feature included in the sponge system is that it uses a bold font for dimensions less than 0.002 inches. It’s a simple signal to the cell members that this dimension is important and should be measured with extra care.

An R on a part number means at some point there was a rejection on that part either internal or external. Part of the standard operating procedure (SOP) on a setup is that any prior rejections are reviewed and signed off on so the same mistake is not made again.

A click on the R brings a history of the reason for the rejection including what went wrong, what was done, corrective action, root cause, the prevention. The machinist signs off electronically that the SOP was read. And to bring home the need to eliminate mistakes, Sponge also shows a risk assessment in the dollar amount that a rejection would cost the company if it made it to a customer. “That’s a powerful incentive,” Mr. Watson says.

This system also houses training SOPs. Arranged to various levels of skills, the training SOP can be used for skill development as employee’s progress through training modules. But it also can be used to refresh previous training.

For example, during an inspection with a pitch mic, a bad dimension turns up. Failed measurement triggers an e-mail to management to find why the mismeasurement occurred and QC comes out to find if additional training for the machinist is needed.

If it is determined the operator wasn’t proficient with a pitch mic, there is a training SOP that describes how to use a pitch mic. The operator is instructed to read the SOP and sign off that the training has taken place. It’s all online and available 24/7 to everyone.

With all the power available from the Sponge system, it’s still just a tool, and it’s dependent on the skill of the people using it. “The human element is still a factor,” says Mr. Watson, “and always will be.” To that end, Acero goes to great ends to find and retain good people. “One of the metrics we try to instill in everyone across the board is make your customer money, and you will be successful,” Mr. Fitzgerald says. “We want people who can understand that.”

Down the Road

Acero is on a growth path. As noted, its business is growing at a significant year over year rate. “We continue to know what’s right and do the right thing,” Mr. Fitzgerald says. “We are in the process of moving from our current four building to a single 80,000-square-foot facility. Our growth is coming mostly from our stable of customers because we are able to do more for them. For example, we have a class 10,000 clean room for assembly and even packaging for medical products. I’m bullish on domestic precision manufacturing. Even though we ship parts twice a week to China and some work we previously did is being made there, we seem to pick up new work to replace it. So far, China has had net zero effect on our business.”

The pursuit of perfection is alive and well at Acero Precision.

RELATED CONTENT

-

Human-Like Robot Automates Secondary Machining Operations

Two seven-axis robots enable two second-op mills to run lights out eight hours in the evenings to win 64 hours of unattended machining time per week for this Ventura, California, shop.

-

Understanding Micro-Milling Machine Technology

Micro-milling can be a companion process to turning-based production machining. This article looks at some of the technologies that go into a micro-milling machine and why they are important to successful operation.

-

Carving Out a Niche in CNC Plastics Machining

This Vermont shop focuses solely on machining plastics — some filled with abrasive glass — for a range of industries. That makes it stand apart from others, but means it also faces challenges that metal machining shops often don’t encounter.