Orders of Magnitude: Key to Process Problem Solving

To solve periodic or intermittent problems in our shops, the first step after identifying the problem is collecting data about when and how often it occurs.

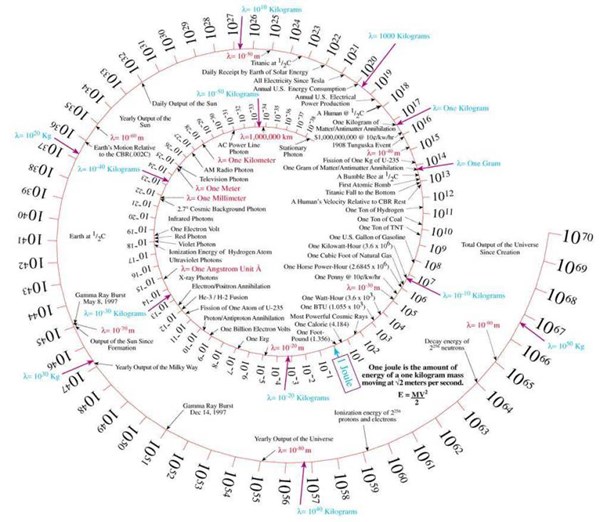

In our shops, order of magnitude reflects the relative scale of our processes and helps us see what is and is not applicable to the problem at hand.

If you have an intermittent or periodic problem, start counting frequency of occurrence, and then figure out what the order of magnitude is compared with your process.

To solve periodic or intermittent problems in our shops, the first step after identifying the problem is collecting data about when and how often it occurs. Then, comparing it with the orders of magnitude that occur naturally in your shop can help you narrow down the likely causes.

Relative frequency can be a big help when you figure out that the frequency has some relationship or equivalence to some aspect of your process. If the frequency is about equal to two occurrences per bar, then it becomes relevant to look at bar ends first, with two ends per bar or the fact that you might get two parts out of the first bar end. This tying of frequency to an order of magnitude denominator saves a lot of thrashing about to try to identify root cause.

What are some orders of magnitude that occur in your shop that you should consider for your problem-solving efforts on intermittent or periodic problems?

Material Order of Magnitude

- Per piece

- Per bar

- Per bundle

- Per lot

- Per order

- Per heat

- Per supplier

Your shop processes have orders of magnitude, too.

Per Machining Operation

- Per spindle

- Per stock up

- Per machine

- Per shift

- Per release

- Per batch

- Per lot

- Per production order

How does this work? In a prior life, I had an intermittent customer complaint for a twisted square bar product. The customer was counting bad pieces cut from bars in bundles. The frequency was extremely low, it was not at one per bar or one per 10 bars, nor one per 20 bars. It turned out to be approximately, slightly less than “one piece per bundle.” Knowing that the frequency was that low, we were able to eliminate most of our upstream of bundle process steps. They would have generated much higher frequencies – more on the order of multiple occurrences per bar.

Based on our frequency being an approximate order of magnitude of one per bundle, we focused our investigation on the product and process at and after the bundle stage, which was where our problem occurred when a single bar end was being twisted by the movement of the last strapping and clip installation as it was tightened for packaging. The balance of the bar was held securely by the prior installed straps, but the tensioning unit grabbed one corner of a bar as it secured the final band around the bars, creating a twist in the end of the bar held under the tension of the clip that locked in that last strap.

Without comparing frequency of occurrence with orders of magnitude in our process, we would probably still be trying to figure out where in our process we could twist only one 14-inch segment out of 3,260 feet of bars. We’d be in denial, and eventually lose the customer.

If you have an intermittent or periodic problem with your products, start counting frequency of occurrence, and then figure out what the order of magnitude is compared with your process.

This article was originally posted on PMPAspeakingofprecision.com blog.

Read Next

Finding the Right Tools for a Turning Shop

Xcelicut is a startup shop that has grown thanks to the right machines, cutting tools, grants and other resources.

Read MoreHow To (Better) Make a Micrometer

How does an inspection equipment manufacturer organize its factory floor? Join us as we explore the continuous improvement strategies and culture shifts The L.S. Starrett Co. is implementing across the over 500,000 square feet of its Athol, Massachusetts, headquarters.

Read More