Applying Multitasking’s Versatility

Already finding success with its milling machines, this shop gained still more productivity when the manufacturer added turning capabilities to the latest models.

The success of a shop’s growth is often based on its approach to new challenges, along with its relationship with suppliers who can help to meet those challenges. As a shop takes on new jobs, it may find that it’s lacking in certain areas that could pose problems in meeting customer expectations. Perhaps the shop’s capacity is too thin to provide the necessary turnaround, or maybe its machines don’t provide the accuracy needed for the finished part.

It’s not uncommon for a shop that is looking to grow to purchase a new piece of equipment that will allow it to land a new customer, but timing needs to be right to ensure that the machine can be installed and up and running quickly enough to meet the customer’s requirements, yet not sit idle for too long waiting for appropriate work.

One shopfloor manager has faced each of these situations before and is using his experience to help his current company grow through implementation of flexible technology that delivers high precision while dropping parts complete.

Learning the Business

Jason McCash grew up learning about machining at his grandfather’s shop. In 2000, he opened his own shop with a CNC lathe and a vertical CNC mill, making medical parts for some engineers he knew. He was busy from the start, quickly adding another vertical CNC mill, along with a couple of employees. But as the parts they worked with became more complex, the small sizes of the parts began to create fixturing issues.

One day in 2006, Bob Shenk, a salesman Mr. McCash knew from his grandfather’s shop, stopped by to see how the business was going. He persuaded Mr. McCash to pay a visit to a shop in Indiana that was running six five-axis mills from Willemin-Macodel. It was a great strategy, as Mr. McCash was able to see first-hand the capabilities of the machines and how they could help his shop. He clearly realized the benefits these machines could provide, but the purchase of even one would be a big investment for his small company. With some apprehension, he moved forward anyway and quickly had one of these mills up and running at his shop. He had such great success with it that through the next five years he purchased five more of these machines.

Not the Plan

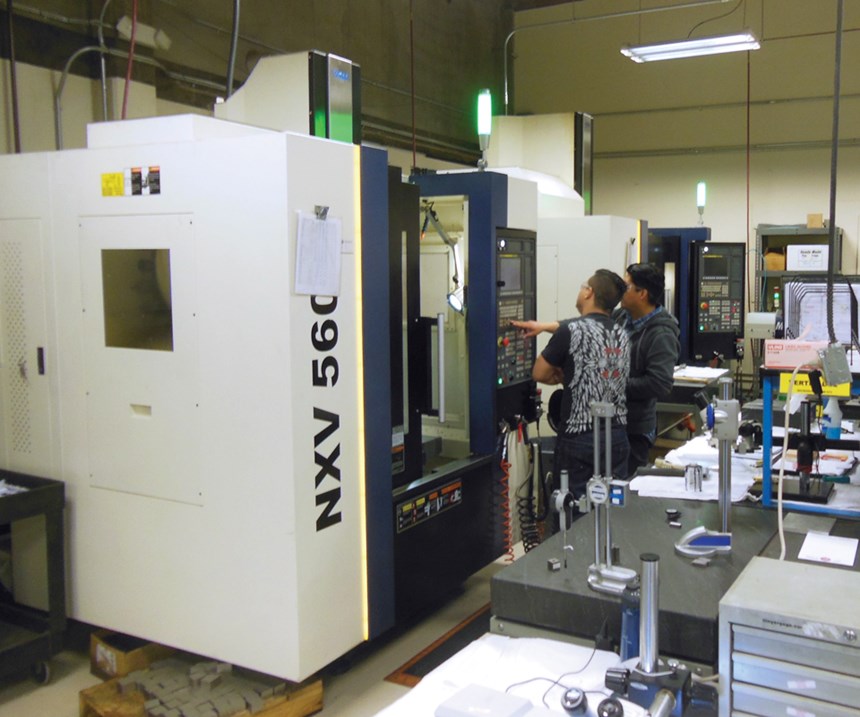

Even with a good plan, things don’t always go as expected. In 2011, Mr. McCash faced some personal challenges that eventually led to the liquidation of his machines and the closure of his business. But his twin sister, Jamie Berg, and her husband, Doug, saw an opportunity and opened their own shop, Berg Manufacturing Inc. (Santa Clara, California). After a substantial investment, Berg began acquiring Willemin machines and eventually hired Mr. McCash as engineering manager to create a manufacturing environment similar to what he previously had in his own company.

Today, Berg Manufacturing is going strong, cranking out parts mainly for the medical industry (with occasional jobs for aerospace, semi-conductor and military). The company specializes in complex prototype parts, but likes when those jobs turn into full production runs. Along with two vertical mills and a Star CNC Swiss-type machine, the company now has six Willemin machines, which Mr. McCash describes as the company’s bread and butter.

The Cost of Doing Business

Operating a business in the Silicon Valley is expensive, with higher wages, workers’ comp, rent and so on. When medical companies are looking for someone to produce a high-production, simpler part, they often send it east where they’re likely to get a better price. For that reason, Berg Manufacturing has focused much of its effort on prototype work. But that doesn’t mean they can’t or won’t do production jobs as well.

Mr. McCash says they go after more complex parts because they have the machines that can handle them and they’re more likely, then, to hold onto them once the job gets to the production stage. He says most shops shy away from the complex parts because they don’t want to deal with the scrap issues in production, but he feels his machines are well built for this type of work and provide the versatility to handle what he throws at them.

“We like when someone comes in with a prototype order of maybe 10 parts that are particularly challenging,” he says. “It allows us to get our process down and determine what it will take to make it.” Then they’re set for accurate quoting as they move into production.

The machines bring another benefit that Mr. McCash says is the key to the shop’s success in its market. Even the most complex parts they take on are dropped complete. Because components are produced from barstock, setup and fixturing is greatly simplified. “The main thing for us is that our parts are so small, we don’t want to have to handle them,” he says. “It works as if a robot is built into the machine, so it maintains the required accuracy without manual repositioning of the parts.”

The Real Advantages

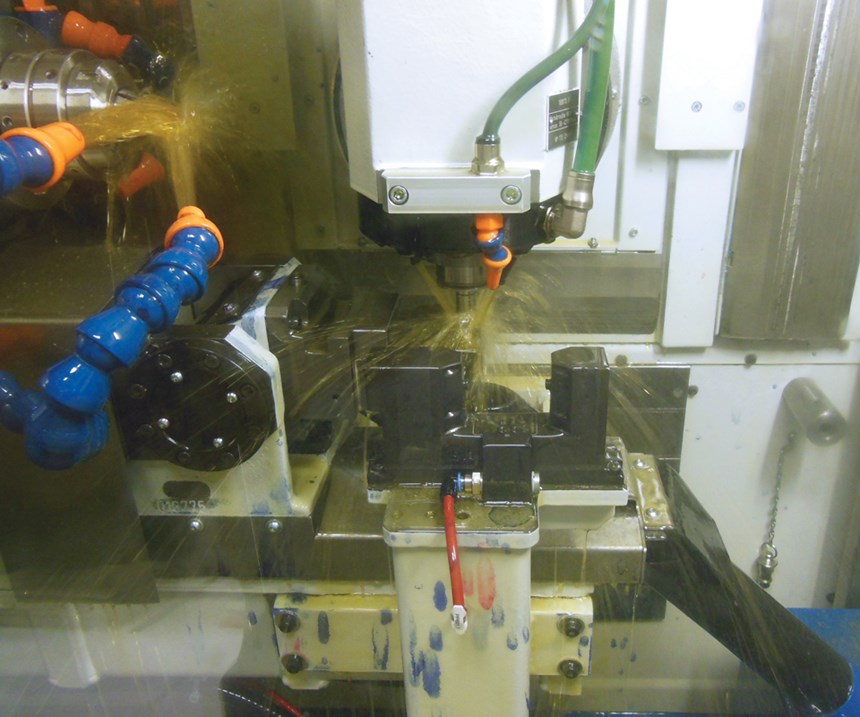

The first Willemin machines that Mr. McCash purchased were 408B models—five-axis bar-fed milling machines with 32-mm diameter bar capacity. The bar feeder pushes the barstock into the machine area to allow the milling spindle to access the part from five sides. A pivoting clamp then swings into position to clamp the part as it is parted off. The part is then repositioned to enable backworking operations on the final side, allowing the part to be dropped complete.

Berg’s lineup of Willemin machines now also includes two 408MT models, which are similar to the B machines except that they include 6,000-rpm turning capabilities on the A axis. A 48-tool magazine accommodates both milling spindles and turning toolholders—a certain number of these are capable of locking the tool, oriented at a certain angle to cut as the spindle turns like a lathe or during shaving and broaching operations. Milling and turning operations can run alternately prior to part cutoff.

These multitasking machines have opened the door for additional work for Berg, giving the company more versatility to produce a wider range of parts. “Certain features are more accurately and more quickly made by turning,” Mr. McCash says. If it’s clearly a screw machine part, it will go on the company’s Star machine, but most of Berg’s parts are milled parts, many of which require turning operations (as much as 20 percent of the part, in some cases). These parts are ideal for the MT machines. “We generally go after parts that are more milling heavy, and Willemins are built for that,” he says. “These machines have a surprisingly rigid spindle for their size, so we’re able to make a heavier cut and remove material faster, yet still get long tool life.” He says he has no problem holding tolerances of a tenth (±0.0001).

Willemin now also offers a 408MTT model, which includes a nine-position turning turret in addition to the five-axis dedicated milling spindle. The turret can house one rotating tailstock center, three axial tools and five radial tools. This setup allows turning operations to be performed while the milling spindle is doing the backworking on a parted off workpiece.

Production Process

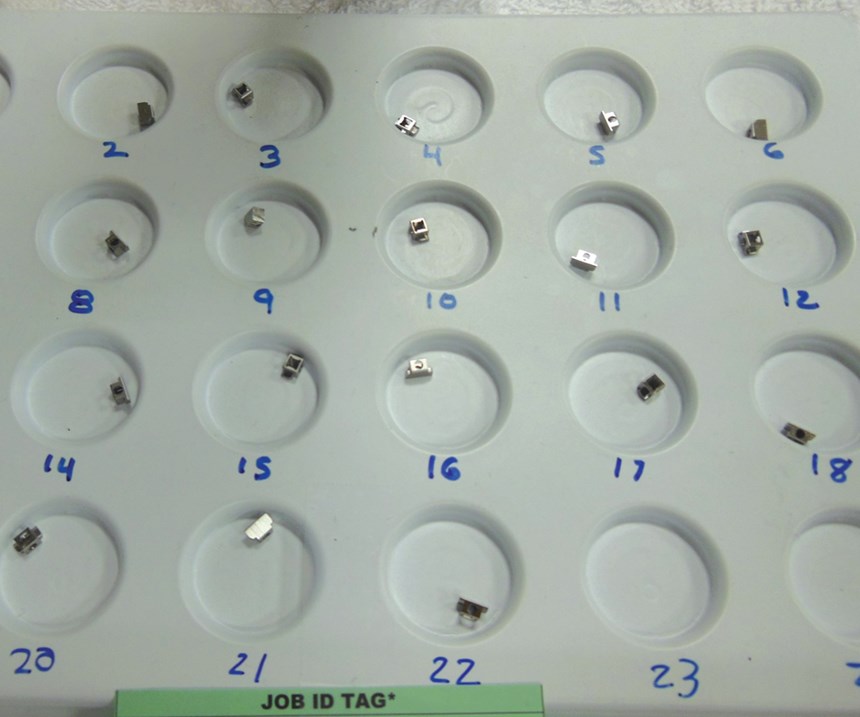

Producing mostly parts for medical instruments, the shop typically works with 17-4 stainless steel, along with tungsten and 304 and 316 stainless. As much as any other industry, quality is key for medical parts. When Mr. McCash programs the parts, he sets them up for in-process checking of any features that could change through the course of the run. Frequency of the inspection is determined by customer quality standards.

“Work and fixture offsets (G54) can shift as the machine warms up,” he says. “Also, with each finish tool, we do a diameter and height check.” Keeping the course, this entire process is automated. The machines include lasers that are used for automated toolsetting and broken tool detection.

Bar feeders of any length can supply material to the machines, allowing long runs of unattended operation. In Berg’s case, bars only a foot and a half in length are fed into the machines. Cycle times of 20 minutes or more on parts of an inch and a half or less in length are common, so the machines still run unattended for considerable stretches (typically about 10 hours and sometimes as long as 30 to 40 hours).

Round barstock is fed through the headstock, and the part is positioned so the A axis can rotate all the way around it. The B axis can rotate as well to allow access to all four sides of the part, and the part can rotate down for access to the face. Once five sides of the part are machined as necessary, the vise pops up and grabs it, the part is cut off, and the vise brings it down for machining the back side. Once complete, the vise opens and the part is dropped down the chute complete.

Berg makes its own blank jaws out of steel and keeps them stocked. Mr. McCash says he considers the jaws part of the consumable of each job, and they generally cannot be reused. The blanks are cut on the other mills, and when a job is set up on a Willemin, the blanks are screwed in and machined to shape before the actual part program starts to run. Every time the job is reset, new blank jaws are set and remachined.

Winning Relationship

The Willemin machines have become the go-to pieces of equipment at Berg Manufacturing, and Mr. McCash feels that not only the machines’ performance, but the service and support he has received from Willemin-Macodel have been instrumental to his company’s ability to bounce back from adversity and thrive in a competitive market. He speaks highly of the relationship he has built with his reps, describing it more as a partnership. “They’ve been willing to work with us when times were tough, and as long as we’re receiving service like this and getting the performance from the machines that we need, it doesn’t make much sense to look elsewhere,” he says.

He also stresses the significance of Willemin-Macodel’s willingness to consider the needs of customers during the development of new models. He has benefited directly from a few of the added features. Beyond the added turning capabilities, the machines now come standard with temperature control of the cutting fluids. By keeping the oil at a steady temperature, the machine remains more stable and performance is far more predictable. He also points out the addition of more coolant lines to direct oil to the cutting area.

“Success is all about relationships,” Mr. McCash says. Berg is in the planning stages to add more equipment, and Mr. McCash is confident that the future will further strengthen his ties to Willemin.

Related Content

Grob Mill-Turn Enhances Process Reliability for Smaller Parts

Grob Systems Inc. introduces the G350T five-axis universal mill-turn center, designed for maximum stability and maintainability in milling and turning operations.

Read More5-Axis Machining Centers Transform Medical Swiss Shop

Traditionally a Swiss machine shop, Swiss Precision Machining Inc. discovers a five-axis machining center that has led the company to substantial growth. (Includes video.)

Read MoreOEM Moves From Automation Implementation to Refinement

Automating challenging parts for full-weekend automation requires substantial process refinements that can significantly boost throughput.

Read More5 Tips for Multichannel Programming

Programming for multitasking machines can be complex. Knowing several key points for making the process less challenging can save a programmer time as well as lessen confusion and the risk of error.

Read MoreRead Next

How To (Better) Make a Micrometer

How does an inspection equipment manufacturer organize its factory floor? Join us as we explore the continuous improvement strategies and culture shifts The L.S. Starrett Co. is implementing across the over 500,000 square feet of its Athol, Massachusetts, headquarters.

Read MoreFinding the Right Tools for a Turning Shop

Xcelicut is a startup shop that has grown thanks to the right machines, cutting tools, grants and other resources.

Read More