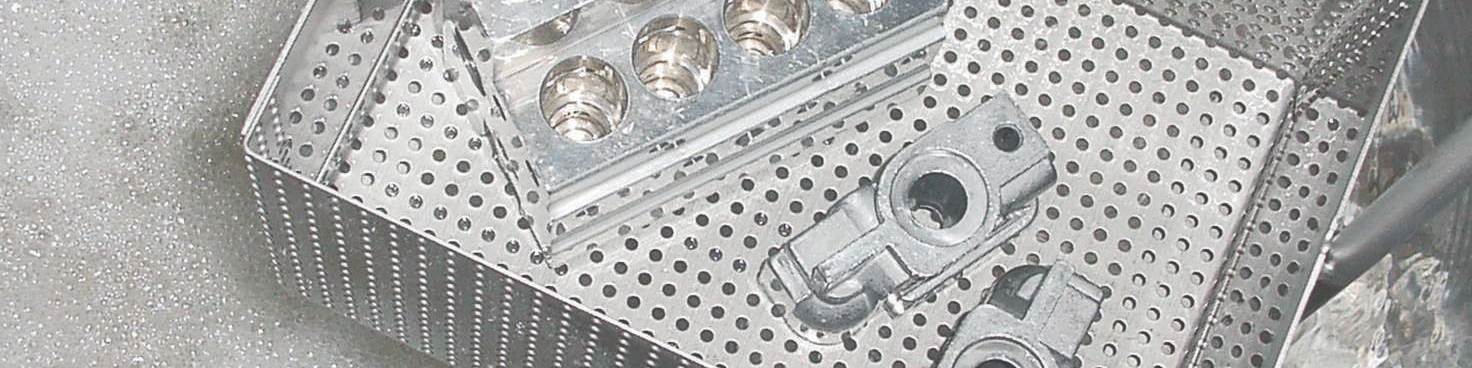

It is critical to understand the chemistry, physics and engineering aspects of cleaning. Knowing the principles of cleaning, including the cleaning agent and the cleaning process, is important, too. Photo Credit: MicroCare

Changing the cleaning process is itself a process that can be overwhelming. Too often the manufacturer becomes enmeshed in a seemingly never-ending cycle of meetings, “quick fixes” that do not work, and a quagmire of company and customer issues. Process selection is put off or an unsuitable selection is made arbitrarily. The manufacturer wastes money, product quality remains suboptimal and there may be lost opportunities for growth. This does not have to happen. Here are some ways to decide which cleaning process to choose and how to get it up and running.

Understand Cleaning Basics

Surface prep is not a mystery. It is critical to understand the chemistry, physics and engineering aspects of cleaning. Knowing the principles of cleaning, including the cleaning agent and the cleaning process, is important, too.

Featured Content

Cleaning is based on TACT (temperature, action, chemistry and time). Cleaning typically improves with higher temperatures because heat improves the solubility of most soils in the cleaning solution. However, there is an upper bound on temperature because high temperatures can damage parts. This suggests there is a “sweet spot” of temperature for optimal cleaning. Action represents the cleaning forces such as scrubbing, spraying or ultrasonics that remove particles and films from a part. Chemistry describes the molecular interactions that clean parts, such as the versatile nature of water, the wetting properties of a surfactant or the solubility characteristics of a solvent. Last, a basic understanding of cleaning involves understanding the role of time — both how long it takes to get a part clean and how long the part was dirty. Letting dirty parts sit almost always makes the cleaning job difficult.

Consider Tact as well as TACT

Why is management demanding a change? What are the goals? What is the time frame? This requires not only TACT but tact. It is best to diplomatically find out what management wants. A request from the boss to “look into what’s out there in cleaning” could mean anything from a mild curiosity to a major problem. This sort of request can elicit one of two responses: The person tasked with cleaning process change might put the request on the back burner and hope for a transfer or promotion. At the other extreme, the person in charge pulls out all the stops and devotes more time and resources than management has in mind.

There are many inspection techniques, from simple white glove inspection to sophisticated particle counting or identification of specific compounds. The best technique may not be the most expensive one. For some applications, visual inspection is sufficient to assure product quality.

Becoming educated about cleaning is advantageous and so is determining not only what management wants but also what manufacturing needs. If improved, product cleaning will lead to higher productivity or will keep the company out of regulatory hot water. It is a good idea to tactfully communicate the options with management.

Clean critically. We have learned to ask questions such as: Is the cleaning process necessary? Can cleaning steps be consolidated? Product cleaning should be a value-added process. What if a company is asked to add or improve an unnecessary or even a counterproductive cleaning process? Cleaning what is not value-added cuts into profitability.

Assess Costs

By providing a budgetary estimate of the full process conversion, it is easier to assess how much management is comfortable spending relative to the cleaning problem to be overcome. New cleaning processes require an investment beyond capital equipment, beyond the initial costs of cleaning agents. Factor in wash, rinse and dry. Drying is often given lip service at best, so the equipment may not be properly sized. A drying step may be needed even for solvents that are self-rinsing.

There are generally costs and issues associated with disposal of spent solvent, spent aqueous cleaner and rinse water. Deionized or RO water may be needed throughout the cleaning process and which the costs of disposal by an outsider provider vary markedly. In general, it costs much more per gallon to dispose of solvent. However, solvent can be used repeatedly. And, if large volumes of rinse water are needed, the disposal costs will increase. For applications using large amounts of rinse water, repurification may be an option. The repurified water may be suitable for release to the publicly owned treatment works or for reuse in cleaning.

Do Not Hope for a Miracle

If there is a yield problem, risk the temptation of a “quick fix.” For example, a co-worker or a sales representative may show up with a new chemical, insisting that it will solve all cleaning problems. Someone may introduce one more step to the process. Not to say there is no such thing as a miracle cure. However, a scattershot approach rarely works. What happens more often is that the process is perceived to improve a bit, but then the problems show up again or becomes worse.

Document the current cleaning agents, equipment, processes and process monitoring. Also, documenting problems can clarify improvement means.

If cleaning equipment breaks down or if higher capacity is required, purchasing the least expensive cleaning equipment or choosing a cleaning agent because the sales rep said to is unlikely to yield effective results.

Listen to what the reps have to say; they understand their product offerings. But that is not enough. It is wise to become the best expert in what is needed. Each worker should know their own product line, customer requirements and all the options. It is less expensive than doing it alone.

Document Procedures

Document the current cleaning agents, equipment, processes and process monitoring. There may be product quality problems associated with certain product configurations or materials of construction. Documenting those problems can clarify improvement means.

Beyond documenting the current cleaning process, demonstrating, documenting and defending what is meant by clean is essential with safety/critical applications and for interacting with inspection groups such as Nadcap and with agencies such as the Food and Drug Administration.

Test, Validate, Inspect

There are many inspection techniques — from simple white glove inspection to sophisticated particle counting or identification of specific compounds. The best technique may not be the most expensive one. For some applications, visual inspection is sufficient to assure product quality. However, it is subjective and should be standardized to make it operational.

Capturing photos of the clean and dirty example parts in the light box with a scale marker and a reference color card will ensure that future parts can be inspected, documented and categorized reliably.

Standardized documentation might include photographic records under controlled conditions along with examples of acceptable and unacceptable cleanliness.

Controlled conditions require controlling the photographic viewing angle, magnification, illumination and background. This can be implemented inexpensively using a light box, camera and tripod. Capturing photos of the clean and dirty example parts in the light box with a scale marker and a reference color card will ensure that future parts can be inspected, documented and categorized reliably.

Foster Teamwork

The person in charge should set up a team that involves the techs or assemblers. If the techs and assemblers do not like the new cleaning process, it will fail. Also, involving the safety/environmental group early on can avoid costly surprises.

Effective cleaning agents may have been banned from the plant by the safety office. Perhaps the quality assurance group must be involved, especially if the final critical cleaning step depends on the processes used by contract manufacturers and job shops.

There must be management buy-in. Management involvement may not mean inviting the president of the company to every team meeting or weighing down their inbox with analyses and brochures. How much involvement depends on the manager and on his/her management style. Short, occasional updates are advised as well as paying attention to the feedback.

Communicate

“Stovepiping” seems to be on the rise. Groups work in isolation and at cross-purposes to each other in government, military and private industry. For precision cleaning processes, this may mean that for each step in the fabrication and build process, one group selects the cleaning agent, another selects cleaning equipment. There can be half a dozen or more such groups or teams within a company. In the interest of supposed efficiency, each team is instructed to handle their own individual task in a sort of vacuum — without considering the overall impact of decisions of any one team on the overall manufacturing effort. Therefore, the production line approach of the Model T Ford era may not be best for critical cleaning of today’s products; it requires greater coordination and communication.

About the Authors

Barbara Kanegsberg and Ed Kanegsberg, Ph.D., of BFK Solutions, are expert consultants in surface quality and process development. Since 1994, they have been working with manufacturers to improve the value of their product through critical and precision cleaning. Contact: info@bfksolutions.com or 310-459-3614.

Darren L. Williams, Ph.D., is the leader of the Cleaning Research Group and professor of physical chemistry at Sam Houston State University. Contact: williams@shsu.edu or 936-294-1529.

RELATED CONTENT

-

4 Considerations for Aerospace Component Cleaning

These pointers for aerospace cleaning can help companies understand best practices, safety and determining part cleanliness.

-

Registration Now Open for 2022 Parts Cleaning Conference

The one-day conference, co-located with IMTS this year, enables attendees to not only learn all things parts cleaning but also to immerse themselves in everything IMTS has to offer.

-

Find Manufacturing Cleaning Webinars Here

Although the pandemic might have made us weary of sitting in front of a screen for too long, webinars still have a significant place in the business world as a quick way to provide education.