Hybrid Multi-Spindle: Look Ma, No Cams

As the volume production market migrates from mechanical multi-spindle machines, builders are creating machine tool technology tiers that apply the correct level of cost and capability to the application.

The multi-spindle production environment continues to change. The debate among precision machined parts manufacturers over flexibility versus dedicated setup goes on.

Increasingly, machine tool builders are designing levels of technical capability that are being applied to the needs of the multi-spindle machine shop. Most multi-spindle shops built their businesses based on high volume runs without the need for much flexibility.

Featured Content

The mechanical multi-spindle automatic is still excellent for these tasks. The problem is that the work for this business model is becoming rarer. Moreover, the skill sets available to set, run and maintain these machines are likewise less abundant.

The venerable multi-spindle concept of progressive machining employing cutters operating on six or eight spindles remains among the most efficient for producing lots of workpieces. So the issue becomes how to deal with the need to change-over the machine more frequently and deal with a dwindling skilled workforce.

To get answers, we traveled up the road to Gosiger High Volume (Dayton, Ohio) to discuss with industry veteran Mark Walker, president, and Mike Moore, national product manager. The timing was good because Gosiger, in collaboration with Japanese builder Shimada, is launching a new jointly developed multi-spindle that Mr. Walker describes as a hybrid machine.

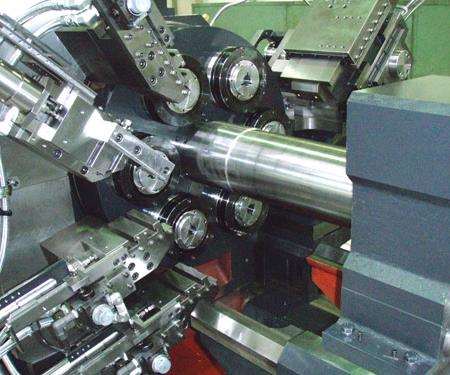

He explains that the hybrid machine is designed to fit a niche in the multi-spindle market between the classic cam-actuated machine and the full CNC multi-spindle. Mr. Walker is quite candid that this new machine is not an “all singing, all dancing” machine like many of the full CNCs on the market, but it doesn’t carry their price tag, either. However, within its target market, the new Shimada provides the production and flexibility for a majority of multi-spindle applications found in shops today. “We wanted to introduce a machine that filled the gap between mechanical machines and full CNC,” Mr. Walker says. “We think the B-27 hybrid does this.”

Who is Shimada?

Shimada has been turning out machine tools (pun intended) since its founding in 1947. It introduced its first multi-spindle and, according the company’s history timeline, Japan’s first multi in 1962.

According to Mr. Walker, for most of its history, the company confined itself to serving the Japanese automotive market. The machines that it sold into the automotive market were chuckers until 1990, when Shimada introduced a bar-fed automatic lathe to augment the chuckers.

Today, Shimada has a full line of two, four, six and eight-spindle machines in its stable. Gosiger has exclusive sales rights to sell the company’s multi-spindle machines in North America. The new Shimada model B-27 hybrid that Gosiger is introducing to the U.S. market is a result of a collaboration between the two companies.

“We worked closely with Shimada in the development of this new machine,” Mr. Walker says. “It worked out well, we knew the U.S. market and its need for a machine in the 27-mm diameter range, which seems to be the sweet spot, and they know how to build multi-spindle machines. To make this collaboration happen, my colleague, Mr. Moore, racked up many miles shuttling between here and Japan to make the project work out to our satisfaction.”

Rotate that Bar

PM has covered the multi-spindle market for many years in the pages of this magazine, and something that stands out are machines that offer independent, programmable spindle speeds and those that do not. There seem to be fewer of the latter. The new machine from Shimada is the company’s first offer of independent spindle capability, which is one of the developments that Gosiger worked with Shimada to develop.

It’s not as easy as it sounds. Powering each spindle is simple enough, but doing so in such a way that allows the carrier drum to index from station to station is the problem. Cam machines don’t deal with this issue because the spindle speeds are not independent.

To overcome this engineering problem, builders have developed different means of accomplishing the task, as one might expect. The system that Shimada and Gosiger settled on is a direct connection between power, lubrication and coolant lines that connect to each of the six, 5-hp, 5,000-rpm direct-drive spindle motors.

This direct connection prevents the drum from rotating more than once. To accommodate this, Shimada, and several other builders, use a reversal system for the drum.

Once the drum indexes to the sixth station, it automatically reverses and begins again. The reversal is fast—1.8 seconds—and has nominal impact on cycle time. Station to station index time is 1.2 seconds.

Because the programmed speeds of each spindle is directly wired from the control to the motor, this becomes an advantage of the reversal system. It allows the spindle to begin an acceleration or deceleration routine to reach its programmed speed while the drum reverses, which helps minimize the impact of the reversal on cycle time.

On any multi-spindle machine, the drum and its spindles are the most critical component for accuracy. Any machinist knows that heat is the enemy of accuracy and that putting six direct-drive motors in the carrier drum is going to generate heat.

In order to stabilize the thermals within the drum, an active mist oil system is used that circulates oil internally through the critical components and is kept at a constant temperature using a chiller.

According to Mr. Moore, what’s driving the multi-spindle technology to integral, independent spindles is the capability they bring to part processing on the machines. “With each spindle directly programmable, shops can stop one or all spindles, program C-axis contouring and constant surface footage as each station’s operations require. These process capabilities, combined with programmable cross and end slides that are easy to program, are causing us to hear more frequently, “You can’t do that on a cam machine.”

Move that Slide

Integral, independent spindle motors are a differentiator between cam multi-spindles and CNC. Being able to program spindle speeds optimally for each station rather than compromising results in better surfaces, longer tool life and shorter cycle time to name a few benefits.

Once each spindle is programmable, it’s the application of CNC to the slides on a multi-spindle that creates some room for debate. Basically, the argument boils down to how much CNC is needed to do the job. One station, two, all stations?

According to Mr. Walker, the Gosiger/Shimada collaboration represented by its hybrid bar machine is purposely targeted to bridge the market gap between cam machines and full CNC multi-spindles. On this machine, the difference is the method of slide actuation.

“Historically creating a hybrid machine meant putting CNC slides on a cam machine,” Mr. Walker says. “While that will work, it still doesn’t solve the issue of making and setting the cams. Our effort with the new hybrid machine is to eliminate cams entirely and replace them with an actuation system that is easy to program and use.

“The new machine uses hydraulic actuation as the replacement of cross and end slide motion,” he continues. “It’s much easier to operate because basically to set the slide requires only a depth and rate setting.”

So for Stations 1 through 4, the cross slide feed is unidirectional, like a cam machine, but instead using cam-less hydraulic actuation. For roughing and semi-finishing operations, traditional multi-spindle tooling can be used, including form tools. The programmable spindles and programmable feed rates allow for optimal metal removal.

Compound CNC slides are used on stations four, five and six. These are CNC servo-driven slides, powered by FANUC motors, through the machine’s FANUC 31i CNC.

“These two-axis slides are programmed independently on a single channel each, just like a two-axis lathe,” Mr. Walker says. “Also, like a two-axis lathe, the stop allows cross drilling, milling and interpolated with the C-axis (30-minute accuracy) contouring.”

Multiple operations can be performed on the Station 4 compound slide with the use of an integral four-tool turret. It can bring turning, threading and grooving tools into the cut at the single station. “This allows us to do more operations at one station without sacrificing cycle time,” Mr. Walker says.

As for backworking, the machine has an independent, servo-driven subspindle to finish off the workpiece. “At this time, the cutter is on a unidirectional slide that is carried on a slanted base for rigidity and access,” Mr. Moore says. “A two-axis backworking slide is in development for applications that may need it.”

In Production

The historic metric for production on a multi-spindle has been cycle time. That is still an important measurement, but increasingly it is being augmented by additional measurements of production.

Mr. Moore believes that production efficiency is as important as cycle time. “These machines run in the high 80- to low 90-percent cut time. They come standard with an integral bar loader, not an add-on, which eliminates the need for feed fingers since it is matched to the machine. The bar feeder is made by P. Cucchi and mated to the new hybrid machine. It can hold 12 to 16 bars in its magazine for additional stock capacity for lights-out machining.”

A driver for the Gosiger/Shimada venture is, in part, the reshoring initiative that is being experienced by many shops. Work is coming back to the U.S. for many reasons, but the bottom line is it’s coming back.

“We’re seeing shops dusting off their banks of multi-spindles in order to tool up for this influx,” Mr. Walker says. “However, many are finding the level of technology they mothballed a few years ago is simply not able to accommodate the accuracy and complexity demands of the available work, not to mention, the skills gap to set and run the machines. We see this machine as a technology bridge that is teachable to today’s workforce and that is able to help continue the momentum of U.S. high volume manufacturing to compete globally.”

Is it for You?

The hybrid multi-spindle is designed to bridge the gap between the limits of conventional cam machines and the capable, but cost-challenging, full CNC counterpart. Finding capable setup operator personnel for cam machines is increasingly difficult, if not impossible. Yet there seems to be a relatively abundant supply of CNC technicians. At least CNC technology is still taught.

Moreover, hybrid technology, designed correctly, can provide a significant percentage of the capabilities found on full CNC machines at a lower cost. There is no doubt that full CNC multi-spindle technology will continue to play a significant role in high volume precision parts manufacturing. However, the hybrid machine concept is designed as a transitional step between mechanical machines and full CNC, giving manufacturers a choice about what level of technology is needed and a means to better match the machine capability to the application.

RELATED CONTENT

-

How Advancements in CNC Multi-Spindles Can Put You Ahead of Current Trends

Growing economic and labor pressures are making CNC multi-spindle turn/mill technology more viable than ever. This real-world comparison to a single-spindle lathe shows how.

-

Turning Machines Help Firearms Supplier Achieve Rapid Growth

Working closely with its machine tool supplier, this firearms manufacturer has quickly expanded its lineup of turning machines to deliver quality products and faster delivery.

-

Large Threading with Single Spindle

Oilfield pipes require large, quality threads. This Texas shop is getting the performance it needs from two recently implemented big bore lathes.