Shop Sticks With Stick Tooling

Who says we can’t be competitive on simple parts? The secret for making it happen at one Connecticut shop is the combination of modern CNC Swiss-type machines and good old-fashioned “stick” tooling.

For all the talk about the simple jobs going overseas “because we can’t make money on them here,” one look at Spargo Machine Products (Terryville, Connecticut) shows that mantra is a myth. A collection of 31 machines, from cam screw machines to CNC lathes to CNC Swiss-types, are all running and monitored by only three people—owner Randy Spargo; his son, Bill; and machine operator, Dennis Drost. To clarify, “simple” doesn’t mean imprecise. All of Spargo’s contracted jobs have some element requiring critical precision. An aluminum tube part, for example, has to be held to within ± 0.0005 inch on the approximate 1-inch length. Competing globally, however, also requires speed. Randy has applied new Swiss-type technology to cut the cycle time on that part in half. Further, he has standardized the programming and tooling. All of the various CNCs use the same resharpenable brazed carbide tooling, which results in faster setup times, faster cycle times, and less tooling costs. All of these elements combined contribute to increased profitability at Spargo.

“Precision and speed are the names in this game,” says Randy Spargo. “The better the machine runs, the less I have to tend to it. The faster the machine runs, the better my prices are to win the jobs. It’s pretty simple.”

Featured Content

Laying Groundwork

Simple philosophy, granted, but this accountant-by-degree, machinist-by-passion guy is a savvy businessman. His shop is a microcosm of machine tool technology evolution. When Randy founded the business in 1986 with his father, William, they started with Brown and Sharpe screw machines. About 10 years later, CNC came into the shop in the form of Supermax lathes. Then Okuma & Howa CNC mill-turns entered the picture in a much larger shop at the company’s current location. The next step was adding more elaborate CNC lathes with subspindles, and ultimately CNC Swiss machines. The most recent additions are two Tsugami Swiss turns—a Model BE-19 automatic lathe, which can also operate as a chucker, and a Model BS-26 C Swiss turn.

“The infrastructure is in place now,” says Randy. “We can easily double our volume with the equipment we have, and we welcome new opportunities. We prefer the simple jobs in softer materials, but we can handle any complex ones in tougher materials also with our new systems.”

An example of a more complex job being produced at Spargo is a stainless interior lock mechanism component. Its features include a milled square, spot drill, tap and tuned diameter on one end. On the back of the part are a 0.204-inch slot and a 0.250-inch diameter off-center hole. Originally, Randy made the part on a conventional CNC lathe. He had to do the turning, then put it in a milling machine to make the slot and drill the hole, re-chuck it in the milling machine to do the flat feature on the other end, and finally put it back on the lathe again for the tapping and finish-turning. When he purchased his mill-turns, he still had to re-chuck to do both ends of the part. From there, it went to the CNC lathe with a Y axis and subspindle, which made the part complete in 4 minutes. Now, the process is accomplished on the Tsugami BS-26 Swiss-turn in 2 minutes—half the time.

“With both of our new Swiss machines, you can program the spindles independently,” says Randy. “I’m able to mill the slot and the off-center hole with the subspindle while the main spindle is working on the front of another part simultaneously. This is where the money is made: by making parts faster.”

Tooling Choices

Making simple parts faster using advanced equipment and a practical approach to tooling are the keys to Spargo’s profitability.

“My father was a Brown and Sharpe screw machine man who lived and breathed quality first and quantity second. He had 70 years of screw machine experience and worked at Spargo Machine every day, up until 3 weeks before he died last July. He passed that knowledge on to me, and I’m now mentoring my son, Bill. I have been the luckiest man alive to grow this business with my dad as my right-hand man. He would often pick up a part being made on one of the CNCs and say with awe, ‘This part could not be made on a Brown and Sharpe.’”

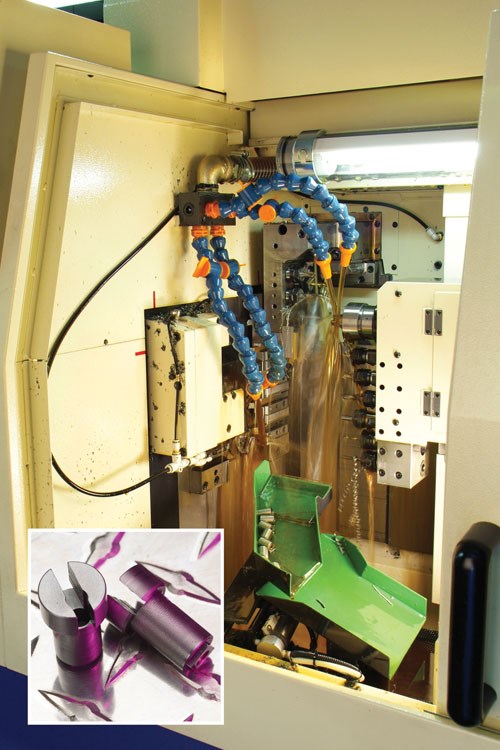

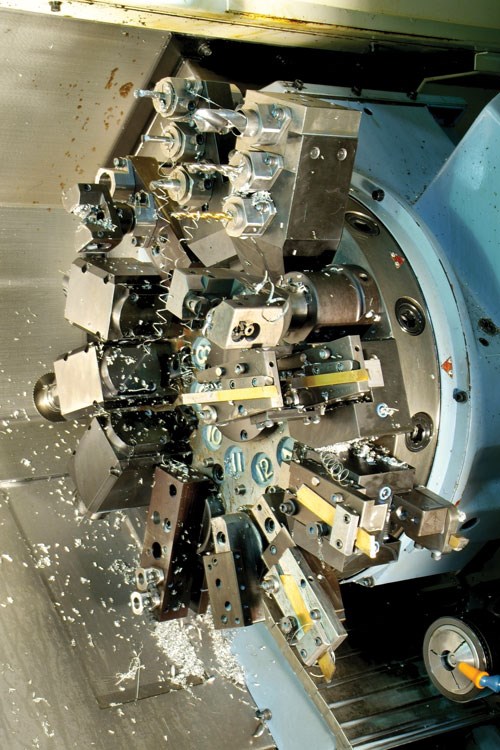

Spargo uses micro-grain carbide “stick” tooling, along with the live mills and drills, on all of the company’s CNC machines. Randy specifies two basic tooling styles that he grinds in an array of angles for his needs: a braised Swiss tool and a large Brown and Sharpe cutoff blade. There is not one cutting tool insert to be found in the shop. His annual tooling costs are $4,000. Using a $10 Swiss tool that can be reground 30 times instead of a single-use insert provides an estimated savings of at least $200,000 per year in tooling costs alone. He has standardized tooling setup on each category of machine, such as his CNC lathes and Swiss-turns, to make programming and setup extremely easy. All of the machines are serviced by bar feeders; some are the magazine style, enabling 24/7 production.

Randy’s tooling knowledge and experience has culminated in a creative way to hold those stick tools and program additional tools in each machine. His custom-designed toolholders can increase the amount of tools at each turret index or stationary position, from two to five. In essence, he has turned his conventional lathes into a gang tool machine on each index. For example, with two tools on one index, he can finish-turn the part, thread, and then deburr all in one index. Randy says that clearance around the back of the turret is the limiting factor on the number of tools he can add. It gets trickier to program multiple tools in one index or position because of interference issues, but according to Randy, once he did it a few times, the programming became easy—as easy as programming one tool. He prefers a “cut, paste and adjust” method of programming rather than the conversational mode in typical CNC software programs.

While the skill of tool grinding is required to apply this atypical strategy, Randy chuckled at a reference to the “age-old art of tool grinding.”

“I taught the so-called ‘age-old art of tool grinding’ to my son in about a day,” he says with chagrin.

Spargo uses archaic-looking manual tool grinders—a roughing grinding wheel, a finish grinding wheel, and a manual Hagar Swiss-type tool grinder with an adjustable angle plate to grind the carbide rakes at different degrees, depending on need. After the first grind of brand new tools, he sends the batch out for titanium-nitride coating. As the machines run and the tools wear, one of the three men in the shop takes the dull tool out, removes about 0.020 inch of material on the roughing wheel, quickly touches it on the finish wheel, bolts it back in the machine, and starts up again. Randy and his team are so proficient at this procedure that it takes about as long to regrind as it does to change an insert.

Prudent Methodology

“A little bit of skill, and I stress ‘little,’ goes a long way to making a shop more profitable,” says Randy. “Plus, this type of tooling makes the machines so much more flexible. I can turn any tool into any width-grooving tool, any kind of threading tool and any kind of finish tool in a matter of minutes. The carbide is higher quality, and the tools are so much more rigid—all important when running fast and long.”

Ultimately Randy has applied a crafted methodology to make his machines more competitive and productive so that he can win the simple jobs that might ordinarily go to China or elsewhere. At the other end of the spectrum, he can take on more complex shaft work in tougher materials with the newest machinery in his shop. When it was time to go to the next level of machine tool technology about a year ago, he was impressed with the Tsugamis for several reasons. First, the BE-19 automatic lathe can operate as a bar or chucker machine by taking the guide bushing out. The BS-26 Swiss-turn can machine complex shafts of as much as 11 inches in length, which will help Randy open his doors to additional work. Both machines, by virtue of their design, can split cycle times in half by working on both ends of a part simultaneously. They also offer coolant-through subspindles, which aid in chip flushing for long runs. Further, Randy was pleased that the machines’ part catchers can go under either the main or subspindle, another plus for simple parts production—there’s no pickoff required to drop the part at the subspindle. He liked the large number of tools and positions available to operate on a part. The BS comes standard with 24, and Randy added another four of his stick tools.

Flexibility, standardization, automation, efficiency, and precision are operational mandates at Spargo Machine Products. They are also the fundamentals, necessities and hallmarks of a smart shop that satisfies customers, makes money and poises itself for growth.

RELATED CONTENT

-

ID and OD Shoe Grinding for Thin-Walled Workpieces

Studer (United Grinding North America) has a solution to the tricky workholding problem of finish grinding close tolerances for roundness and concentricity of thin-walled rings and sleeves or a rolling element such as a bearing raceway.

-

Centerless Grinding Achieves Precision Roundness

Knowing the basics of centerless grinding is an important step to making it a successful operation in your shop.

-

Manufacturing Efficiently at a Micron Level

Grinding very small-diameter instruments for use in medical procedures is a niche business for this micro-grinding machine manufacturer. The company makes machines that use a variety of grinding techniques to manufacture guidewires for the medical industry.

.jpg;width=550;quality=60)